Quick Reference

Magazine Capacity Restrictions

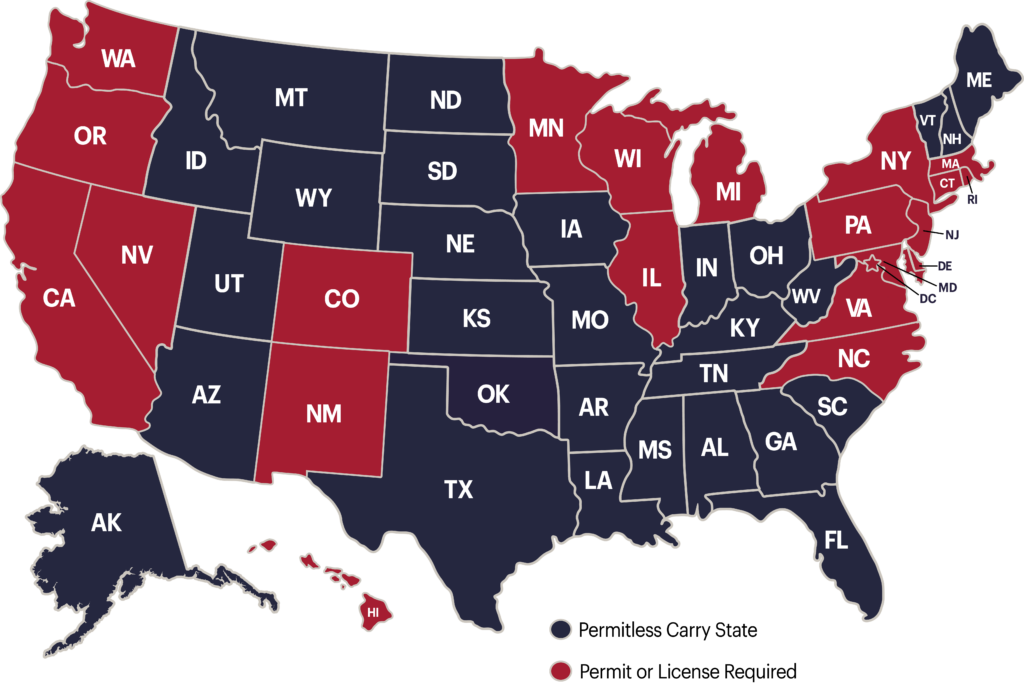

Constitutional (Permitless) Carry Allowed

Red Flag Laws

Carry in Alcohol Establishments Allowed

Open Carry Allowed

No Weapons Signs Enforced by Law

NFA Weapons Allowed

Duty to Retreat

Duty to Inform Law Enforcement

"Universal" Background Checks Required

Table of Contents

State Law Summary

Constitution of the State of Pennsylvania - Pa. Const. Art. I, § 21

"The right of the citizens to bear arms in defense of themselves and the State shall not be questioned."

In 1995, the legislature made significant amendments to its Uniform Firearms Act, with the relevant subchapter now formally referred to as the "Pennsylvania Uniform Firearms Act of 1995." The Pennsylvania Uniform Firearms Act regulates the ownership, possession, transportation and transfer of firearms. This includes the conduct that requires a License to Carry Firearms (concealed carry permit) and the process by which the issuing authority must abide. Aside from the Uniform Firearms Act, Title 18, Chapter 5 of the Pennsylvania Statutes and Codified Statutes codifies the justified use of force and deadly force, highlighting the importance of self-defense and the limited circumstances under which such force is justified. Additionally, through 18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. § 6120, the legislature has codified preemption of firearms laws, and multiple court cases have affirmed that local governments do not have the authority to regulate ownership, possession, transportation or transfer of firearms. Overall, while Pennsylvania's firearm laws reflect an acknowledgement of one's fundamental right to bear arms, they also include a number of complex restrictions and regulations.

Permit Eligibility, Training and Application Process

Pennsylvania's history of licenses to carry firearms has evolved significantly over the years. Though older laws required an applicant to show a justifiable need for a License to Carry Firearms, the Uniform Firearms Act of 1995 has no such requirement. Currently, Pennsylvania law requires individuals to apply for a license and includes a background check through the Pennsylvania Instant Check System. The issuing authority may also conduct an investigation regarding the applicant's "character and reputation" (see below), though the application must be approved or denied within 45 days. Issuing authorities are now permitted to accept online applications, which improves accessibility for applicants, though not all issuing authorities provide this option. Notably, many local governments who have attempted to illegally create their own firearms ordinances have faced legal challenges, but the rulings consistently emphasize the preemption of state law over local ordinances.

License to Carry Firearms (Permit) Eligibility

- By statute, all applicants must be at least 21 years of age. * This requirement was held unconstitutional in Lara v. PSP Commissioner (3rd Circuit). It is uncertain whether this case will proceed to the Supreme Court of the United States.

- All applicants must complete the Application for a Pennsylvania License to Carry Firearms.

- Pennsylvania residents must possess a valid Pennsylvania Driver's License or Identification Card.

- Out of state residents are required to accompany their application with a full color copy of their domicile state valid Driver's License and Concealed Weapons Permit.

- There is no training requirement in Pennsylvania.

- There are many reasons for which a person can be ineligible for a License to Carry Firearms, independent of whether a person is eligible to own and possess firearms under federal law. The reasons for ineligibility may include:

- (i) An individual whose character and reputation is such that the individual would be likely to act in a manner dangerous to public safety. *Note: this criteria is subjectively determined by the issuing authority.

- (ii) An individual who has been convicted of an offense under the act of April 14, 1972 (P.L.233, No.64), known as The Controlled Substance, Drug, Device and Cosmetic Act. *Note: This includes any offense, not just those which would prohibit one from possessing firearms under federal law.

- (iii) An individual convicted of a crime enumerated in 18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. § 6105.

- (iv) An individual who, within the past ten years, has been adjudicated delinquent for a crime enumerated in 18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. § 6105 or for an offense under The Controlled Substance, Drug, Device and Cosmetic Act.

- (v) An individual who is not of sound mind or who has ever been committed to a mental institution.

- (vi) An individual who is addicted to or is an unlawful user of marijuana or a stimulant, depressant or narcotic drug.

- (vii) An individual who is a habitual drunkard.

- (viii) An individual who is charged with or has been convicted of a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year except as provided for in 18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. § 6123 (relating to waiver of disability or pardons).

- (ix) A resident of another state who does not possess a current license or permit or similar document to carry a firearm issued by that state if a license is provided for by the laws of that state, as published annually in the Federal Register by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms of the Department of the Treasury under 18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(19) (relating to definitions).

- (x) An alien who is illegally in the United States.

- (xi) An individual who has been discharged from the armed forces of the United States under dishonorable conditions.

- (xii) An individual who is a fugitive from justice. This subparagraph does not apply to an individual whose fugitive status is based upon nonmoving or moving summary offense under Title 75 (relating to vehicles).

- (xiii) An individual who is otherwise prohibited from possessing, using, manufacturing, controlling, purchasing, selling or transferring a firearm as provided by 18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. § 6105.

- (xiv) An individual who is prohibited from possessing or acquiring a firearm under the statutes of the United States.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6106

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6109

PA License Application Process

- Do not apply unless you are certain you meet the eligibility criteria. Providing an inaccurate response on a License to Carry Firearms could result in criminal prosecution under 18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. § 4904.

- If you are a Pennsylvania resident, you must apply for your License to Carry Firearms in the county in which you reside. The issuing authority for a License to Carry Firearms is the County Sheriff, or in Philadelphia, the Chief of Police (through the Philadelphia Police Department "Gun Permit Unit"). Check the issuing authority's website to determine whether online applications are accepted, or whether you must apply in person. Note: Many counties do not accept applications from non-residents, an issue which may soon be litigated. The issuing authority's website will likely outline the information necessary to complete your application (e.g., Driver's License/State ID, forms of payment accepted, name/contact information of two non-family references).

- Cost is $20.00 (some counties charge a service fee if paying by credit/debit card).

- The issuing authority must, by statute, approve or deny within 45 days. In practice, many provide their response sooner.

- The License to Carry Firearms is valid for 5 years.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6109

Training Requirements:

Pa. OAG Informal Guidance (2012) confirms Pennsylvania has no statutory training mandate for LTCF issuance; warns that students traveling to other states should check training requirements under reciprocity agreements.

Permitless Carry Law

The terms “constitutional carry” and “permitless carry” refer to states that have laws allowing individuals to carry a loaded firearm in public without requiring a license or permit.

Pennsylvania is not a permitless-carry state.

Reciprocity Agreements

Reciprocity refers to an agreement between states to recognize, or honor, a concealed firearm permit issued by another state.

When you are in another state, you are subject to that state’s laws. Even if a state recognizes your carry permit or allows for permitless carry, the state may have additional restrictions on certain types of firearms, magazines, or ammunition. Take time to learn the law!

State Preemption Laws

State firearm preemption laws are statutes that prevent local governments from enacting or enforcing their own gun regulations that are more restrictive than state law. These laws ensure that firearm regulations remain consistent across the state, preventing a patchwork of different rules in various cities or counties.

Pennsylvania law:

Title 18, Section 6108 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes states:

No person shall carry a firearm, rifle or shotgun at any time upon the public streets or upon any public property in a city of the first class unless:

(1) such person is licensed to carry a firearm; or

(2) such person is exempt from licensing under section 6106(b) of this title (relating to firearms not to be carried without a license).

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6108

(1) Engage in any proprietary or private business except as authorized by statute.

(2) Exercise powers contrary to or in limitation or enlargement of powers granted by statutes which are applicable in every part of this Commonwealth.

(3) Be authorized to diminish the rights or privileges of any former municipal employee entitled to benefits or any present municipal employee in his pension or retirement system.

(4) Enact or promulgate any ordinance or regulation with respect to definitions, sanitation, safety, health, standards of identity or labeling pertaining to the manufacture, processing, storage, distribution and sale of any foods, goods or services subject to any Commonwealth statutes and regulations unless the municipal ordinance or regulation is uniform in all respects with the Commonwealth statutes and regulations thereunder. This paragraph does not affect the power of any municipality to enact and enforce ordinances relating to building codes or any other safety, sanitation or health regulation pertaining thereto.

(5) Enact any provision inconsistent with any statute heretofore enacted prior to April 13, 1972, affecting the rights, benefits or working conditions of any employee of a political subdivision of this Commonwealth.

53 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 2962(c)

Statutes of general application.

Statutes that are uniform and applicable in every part of this Commonwealth shall remain in effect and shall not be changed or modified by this subpart. Statutes shall supersede any municipal ordinance or resolution on the same subject.

53 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 2962(e)

Regulation of firearms.

A municipality shall not enact any ordinance or take any other action dealing with the regulation of the transfer, ownership, transportation or possession of firearms.

53 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 2962(g)

Purchase/Transfer Laws

When buying or selling a firearm, both federal and state laws must be followed. Under 18 U.S.C. § 922(a)(5), a private party may sell a firearm to a resident of the same state if two conditions are met: (1) the seller and buyer must be residents of the same state, and (2) the seller must not know or have reasonable cause to believe that the buyer is prohibited from receiving or possessing firearms under federal law, as outlined in 18 U.S.C. § 922(g).

Additionally, a private seller may loan or rent a firearm to a resident of any state for temporary lawful sporting use, provided they meet the same condition of not knowing or having reason to believe the borrower is prohibited under federal law.

In addition to federal law, state laws governing firearm sales must also be followed, as states may impose additional restrictions such as background checks, waiting periods, or bans on specific types of firearms.

PA Private-Party Firearm Transfers

In Pennsylvania, a private party may only sell a handgun or short-barreled rifle or shotgun to an unlicensed purchaser at the place of business of a licensed importer, manufacturer, dealer or county sheriff’s office.

- The licensed importer, manufacturer, dealer or sheriff must comply with all of the dealer regulations, including a background check on prospective purchaser.

- These requirements do not apply to transfers between spouses, parents and children, or grandparents and grandchildren. These requirements also do not generally apply to transfers of long guns.

- Any seller who knowingly and intentionally delivers a firearm to an individual who is not eligible to possess a firearm commits a third degree felony.

- No seller may deliver a handgun or short-barreled rifle or shotgun to the purchaser or transferee unless the firearm is securely wrapped and unloaded.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6111(c)

Notwithstanding any section of this chapter to the contrary, nothing in this chapter shall be construed to allow any government or law enforcement agency or any agent thereof to create, maintain or operate any registry of firearm ownership within this Commonwealth. For the purposes of this section only, the term "firearm" shall include any weapon that is designed to or may readily be converted to expel any projectile by the action of an explosive or the frame or receiver of any such weapon.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6111.4

Nothing in this chapter shall be construed to prohibit a person in this Commonwealth who may lawfully purchase, possess, use, control, sell, transfer or manufacture a firearm which exceeds the barrel and related lengths set forth in section 6102 (relating to definitions) from lawfully purchasing or otherwise obtaining such a firearm in a jurisdiction outside this Commonwealth.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6141.1

Firearm Classification and Accessory Restrictions

(a) Offense defined.--A person commits a misdemeanor of the first degree if, except as authorized by law, he makes repairs, sells, or otherwise deals in, uses, or possesses any offensive weapon.

(b) Exceptions.--

(1) It is a defense under this section for the defendant to prove by a preponderance of evidence that he possessed or dealt with the weapon solely as a curio or in a dramatic performance, or that, with the exception of a bomb, grenade or incendiary device, he complied with the National Firearms Act (26 U.S.C. § 5801 et seq.), or that he possessed it briefly in consequence of having found it or taken it from an aggressor, or under circumstances similarly negativing any intent or likelihood that the weapon would be used unlawfully.

(2) This section does not apply to police forensic firearms experts or police forensic firearms laboratories. Also exempt from this section are forensic firearms experts or forensic firearms laboratories operating in the ordinary course of business and engaged in lawful operation who notify in writing, on an annual basis, the chief or head of any police force or police department of a city, and, elsewhere, the sheriff of a county in which they are located, of the possession, type and use of offensive weapons.

(3) This section shall not apply to any person who makes, repairs, sells or otherwise deals in, uses or possesses any firearm for purposes not prohibited by the laws of this Commonwealth.

(c) Definitions.--As used in this section, the following words and phrases shall have the meanings given to them in this subsection:

“Firearm.” Any weapon which is designed to or may readily be converted to expel any projectile by the action of an explosive or the frame or receiver of any such weapon.

“Offensive weapons.” Any bomb, grenade, machine gun, sawed-off shotgun with a barrel less than 18 inches, firearm specially made or specially adapted for concealment or silent discharge, any blackjack, sandbag, metal knuckles, any stun gun, stun baton, taser or other electronic or electric weapon or other implement for the infliction of serious bodily injury which serves no common lawful purpose.

(d) Exemptions.--The use and possession of blackjacks by the following persons in the course of their duties are exempt from this section:

(1) Police officers, as defined by and who meet the requirements of the act of June 18, 1974 (P.L. 359, No. 120), referred to as the Municipal Police Education and Training Law.1

(2) Police officers of first class cities who have successfully completed training which is substantially equivalent to the program under the Municipal Police Education and Training Law.

(3) Pennsylvania State Police officers.

(4) Sheriffs and deputy sheriffs of the various counties who have satisfactorily met the requirements of the Municipal Police Education and Training Law.

(5) Police officers employed by the Commonwealth who have satisfactorily met the requirements of the Municipal Police Education and Training Law.

(6) Deputy sheriffs with adequate training as determined by the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency.

(7) Liquor Control Board agents who have satisfactorily met the requirements of the Municipal Police Education and Training Law.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 908

- Short-Barreled Rifles & Shotguns (SBR/SBS) – Regulated by the National Firearms Act (NFA); legal in PA if federally registered (18 Pa.C.S. § 908).

- Machine Guns – Legal in PA if federally registered (§ 908).

- "Offensive Weapons" – PA bans certain weapons under § 908 unless possessed for lawful purposes (e.g., NFA registration for suppressors, SBRs).

- Armor-Piercing Ammunition – Restricted under § 6121 for criminal use; no ban on mere possession by non-prohibited persons.

(a) Offense defined.--Except as set forth in subsection (b), a person commits an offense if the person does any of the following:

(1) Uses an electric or electronic incapacitation device on another person for an unlawful purpose.

(2) Possesses, with intent to violate paragraph (1), an electric or electronic incapacitation device.

(b) Self defense.--A person may possess and use an electric or electronic incapacitation device in the exercise of reasonable force in defense of the person or the person's property pursuant to Chapter 5 (relating to general principles of justification) if the electric or electronic incapacitation device is labeled with or accompanied by clearly written instructions as to its use and the damages involved in its use.

(c) Prohibited possession.--No person prohibited from possessing a firearm pursuant to section 6105 (relating to persons not to possess, use, manufacture, control, sell or transfer firearms) may possess or use an electric or electronic incapacitation device.

(d) Grading.--An offense under subsection (a) shall constitute a felony of the second degree if the actor acted with the intent to commit a felony. Otherwise any offense under this section is graded as a misdemeanor of the first degree.

(e) Exceptions.--Nothing in this section shall prohibit the possession or use by, or the sale or furnishing of any electric or electronic incapacitation device to, a law enforcement agency, peace officer, employee of a correctional institution, county jail or prison or detention center, the National Guard or reserves or a member of the National Guard or reserves for use in their official duties.

(f) Definition.--As used in this section, the term “electric or electronic incapacitation device” means a portable device which is designed or intended by the manufacturer to be used, offensively or defensively, to temporarily immobilize or incapacitate persons by means of electric pulse or current, including devices operating by means of carbon dioxide propellant. The term does not include cattle prods, electric fences or other electric devices when used in agricultural, animal husbandry or food production activities.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 908.1

Magazine Capacity Restrictions

Magazine capacity laws are designed to limit the number of rounds a firearm's magazine can hold, typically restricting it to a certain number of cartridges (e.g., 10 rounds or fewer). Some state laws restrict the amount of rounds that may be placed in a magazine at any given time, while others prevent the mere possession of unloaded magazines capable of accepting more than a certain number of rounds.

Pennsylvania has no laws restricting the ammunition capacity of magazines.

Prohibited Areas - Where Firearms Are Prohibited Under State law

Carrying a firearm into a place where firearms are prohibited by state or federal law is a common way for gun owners to find themselves in legal trouble. These places are known as “prohibited areas,” and they can vary greatly from state to state.

Below you will find the list of the places where firearms are prohibited under this state’s laws. Keep in mind, in addition to these state prohibited areas, federal law adds additional places where firearms are prohibited. See the federal law section for a list of federal prohibited areas.

Firearms are not allowed in the following locations:

- Courthouses (18 Pa. Cons. Stat. §913)

- Public and private school property (18 Pa. Cons. Stat. §912)

- Detention centers (police, sheriff, and prison) (61 Pa. Cons. Stat. §5902)

- Mental hospital (18 Pa. Consol. Stat. Ann. § 5122)

- The Capitol Complex (49 Pa. Cons. Stat. §61.1)

- The possession of firearms or other prohibited offensive weapons as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 908(c) (relating to prohibited offense weapons), while on the leased premises of the Department with the exception of State or Federal officers, in connection with the performance of an official duty, is prohibited. This prohibition does not apply to attorneys listed as counsel of record in connection with the offering of an exhibit in any administrative proceeding, if the counsel of record who intends to offer the item as an exhibit, has obtained written authorization from a hearing examiner to do so. 49 Pa. Code § 61.3

(d) Posting of notice.--Notice of the provisions of subsections (a) and (e) shall be posted conspicuously at each public entrance to each courthouse or other building containing a court facility and each court facility, and no person shall be convicted of an offense under subsection (a)(1) with respect to a court facility if the notice was not so posted at each public entrance to the courthouse or other building containing a court facility and at the court facility unless the person had actual notice of the provisions of subsection (a).

(e) Facilities for checking firearms or other dangerous weapons.--Each county shall make available at or within the building containing a court facility by July 1, 2002, lockers or similar facilities at no charge or cost for the temporary checking of firearms by persons carrying firearms under section 6106(b) or 6109 or for the checking of other dangerous weapons that are not otherwise prohibited by law. Any individual checking a firearm, dangerous weapon or an item deemed to be a dangerous weapon at a court facility must be issued a receipt. Notice of the location of the facility shall be posted as required under subsection (d).

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 913

Methods of Carry - Open Carry Laws

Open carry and concealed carry refer to two distinct methods of carrying firearms in public. Open carry involves visibly carrying a firearm, typically in a holster, where it is easily seen by others. Concealed carry, on the other hand, involves carrying a firearm in a hidden manner, such as under clothing, so that it is not visible to others.

In Pennsylvania, persons who are not prohibited by law from owning firearms may openly carry a handgun in plain sight with no license except in vehicles, cities of the first class (Philadelphia), and where prohibited specifically by law.

- Open carry (of a handgun) in a vehicle requires a valid PA LTCF or a carry license from ANY other state.

- Open carry in Philadelphia requires a valid PA LTCF or a reciprocal state’s carry license.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6106, §6107, §6108

No Weapons Signs

"No weapons" signs are notices posted by businesses or private property owners indicating that firearms or other weapons are not allowed on the premises. The legal impact of these signs varies by state. In some states, these signs have the force of law, meaning that if a person carries a weapon onto the property in violation of the sign, they can face criminal penalties such as fines or arrest. In these states, ignoring a "no weapons" sign can result in legal consequences similar to trespassing.

In other states, however, these signs are merely a business's policy, and while a person carrying a weapon might be asked to leave, there are no legal penalties for entering with a weapon unless they refuse to leave when asked, at which point trespassing laws may apply.

Defiant Trespasser

(1) A person commits an offense if, knowing that he is not licensed or privileged to do so, he enters or remains in any place as to which notice against trespass is given by:

- (i) actual communication to the actor;

- (ii) posting in a manner prescribed by law or reasonably likely to come to the attention of intruders;

- (iii) fencing or other enclosure manifestly designed to exclude intruders;

- (iv) notices posted in a manner prescribed by law or reasonably likely to come to the person's attention at each entrance of school grounds that visitors are prohibited without authorization from a designated school, center or program official; or

- (v) an actual communication to the actor to leave school grounds as communicated by a school, center or program official, employee or agent or a law enforcement officer.

(2) Except as provided in paragraph (1)(v), an offense under this subsection constitutes a misdemeanor of the third degree if the offender defies an order to leave personally communicated to him by the owner of the premises or other authorized person. An offense under paragraph (1)(v) constitutes a misdemeanor of the first degree. Otherwise it is a summary offense.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3503(b)

Controlled Substance/Alcohol Laws

Most, but not all, states have laws in place that regulate possessing firearms while intoxicated, and individual states will define "intoxicated" differently. In addition to state law, federal law also prohibits the possession of a firearm by any person who is “an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance” as defined by the Controlled Substances Act (“CSA”). There are five different schedules of controlled substances regulated by the CSA, scheduled as I–V. The types of drugs that are regulated range from heroin as a Schedule I substance, to Robitussin AC as a Schedule V substance. Even a gun owner that is prescribed a scheduled drug by a physician can be in legal jeopardy if it is proven that the drug was taken in a frequency or manner other than was prescribed.

Although legal for medicinal or recreational use in many states, marijuana remains classified as a scheduled controlled substance under the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA), codified as 21 U.S.C. § 812. On May 16, 2024, the U.S. Department of Justice published a proposed rule change that would reclassify marijuana from schedule I to a schedule III drug. It is anticipated this rescheduling will formally occur in 2024 or 2025. Unlike schedule I drugs, schedule III drugs may be lawfully prescribed by a licensed physician, and thus the possession of these prescribed drugs does not make the possession of a firearm inherently unlawful the way possession of a schedule I substance would. This means that the rescheduling of marijuana to a schedule III drug would finally allow for the lawful use, possession and purchase of firearms by prescription marijuana users. However, if it is determined that the marijuana is possessed without a prescription, is used in a manner that is not prescribed, or that the individual with the prescription is addicted to marijuana, possession of a firearm would still be a federal offense. Federal law states that a person is addicted to a controlled substance when they have “lost the power of self-control with reference to the use of controlled substance; and any person who is a current user of a controlled substance in a manner other than as prescribed by a licensed physician.”

27 C.F.R. § 478.11, 18 U.S.C. §922(g)(3)

Issuance of License:

(1) A license to carry a firearm shall be for the purpose of carrying a firearm concealed on or about one's person or in a vehicle and shall be issued if, after an investigation not to exceed 45 days, it appears that the applicant is an individual concerning whom no good cause exists to deny the license. A license shall not be issued to any of the following:

- (i) An individual whose character and reputation is such that the individual would be likely to act in a manner dangerous to public safety.

- (ii) An individual who has been convicted of an offense under the act of April 14, 1972 (P.L.233, No.64), known as The Controlled Substance, Drug, Device and Cosmetic Act.

- (iv) An individual who, within the past ten years, has been adjudicated delinquent for a crime enumerated in section 6105 or for an offense under The Controlled Substance, Drug, Device and Cosmetic Act.

- (vi) An individual who is addicted to or is an unlawful user of marijuana or a stimulant, depressant or narcotic drug.

- (vii) An individual who is a habitual drunkard.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6109(e)

Vehicle and Transport Laws

Permit reciprocity and other differences between state regulation of firearms can create a difficult landscape for firearm owners to navigate while transporting firearms interstate. In 1968, and again in 1986, Congress set out to help hunters, travelers, and other firearm owners who were getting arrested for merely transporting firearms through restrictive states. To help simplify the complex web of state firearm laws, Congress passed the 1986 Firearm Owners Protection Act (“FOPA”) as part of Senate Bill 2414. The specific “safe harbor” provision of the law, often referred to as the “McClure-Volkmer Rule,” provides some protection for gun owners transporting firearms through restrictive states, subject to strict requirements. This federal law is covered in more detail in the federal law section of this database.

Beyond federal law, the laws of each state will impose additional restrictions, or protections, related to transporting firearms in a vehicle. You can’t carry a loaded firearm in a vehicle unless you have a permit issued by Pennsylvania or any other state. Open carry is legal in Pennsylvania without a permit but you must have a permit to carry a firearm in a vehicle. See (11) and (15) below in statute Title 18 § 6106.

(a) Offense Defined

(1) Except as provided in paragraph (2), any person who carries a firearm in any vehicle or any person who carries a firearm concealed on or about his person, except in his place of abode or fixed place of business, without a valid and lawfully issued license under this chapter commits a felony of the third degree.

(2) A person who is otherwise eligible to possess a valid license under this chapter but carries a firearm in any vehicle or any person who carries a firearm concealed on or about his person, except in his place of abode or fixed place of business, without a valid and lawfully issued license and has not committed any other criminal violation commits a misdemeanor of the first degree.

(b) Exceptions.--The provisions of subsection (a) shall not apply to:

(1) Constables, sheriffs, prison or jail wardens, or their deputies, policemen of this Commonwealth or its political subdivisions, or other law-enforcement officers.

(2) Members of the army, navy, marine corps, air force or coast guard of the United States or of the National Guard or organized reserves when on duty.

(3) The regularly enrolled members of any organization duly organized to purchase or receive such firearms from the United States or from this Commonwealth.

(4) Any persons engaged in target shooting with a firearm, if such persons are at or are going to or from their places of assembly or target practice and if, while going to or from their places of assembly or target practice, the firearm is not loaded.

(5) Officers or employees of the United States duly authorized to carry a concealed firearm.

(6) Agents, messengers and other employees of common carriers, banks, or business firms, whose duties require them to protect moneys, valuables and other property in the discharge of such duties.

(7) Any person engaged in the business of manufacturing, repairing, or dealing in firearms, or the agent or representative of any such person, having in his possession, using or carrying a firearm in the usual or ordinary course of such business.

(8) Any person while carrying a firearm which is not loaded and is in a secure wrapper from the place of purchase to his home or place of business, or to a place of repair, sale or appraisal or back to his home or place of business, or in moving from one place of abode or business to another or from his home to a vacation or recreational home or dwelling or back, or to recover stolen property under section 6111.1(b)(4) (relating to Pennsylvania State Police), or to a place of instruction intended to teach the safe handling, use or maintenance of firearms or back or to a location to which the person has been directed to relinquish firearms under 23 Pa.C.S. § 6108 (relating to relief) or back upon return of the relinquished firearm or to a licensed dealer's place of business for relinquishment pursuant to 23 Pa.C.S. § 6108.2 (relating to relinquishment for consignment sale, lawful transfer or safekeeping) or back upon return of the relinquished firearm or to a location for safekeeping pursuant to 23 Pa.C.S. § 6108.3 (relating to relinquishment to third party for safekeeping) or back upon return of the relinquished firearm.

(9) Persons licensed to hunt, take furbearers or fish in this Commonwealth, if such persons are actually hunting, taking furbearers or fishing as permitted by such license, or are going to the places where they desire to hunt, take furbearers or fish or returning from such places.

(10) Persons training dogs, if such persons are actually training dogs during the regular training season.

(11) Any person while carrying a firearm in any vehicle, which person possesses a valid and lawfully issued license for that firearm which has been issued under the laws of the United States or any other state.

(12) A person who has a lawfully issued license to carry a firearm pursuant to section 6109 (relating to licenses) and that said license expired within six months prior to the date of arrest and that the individual is otherwise eligible for renewal of the license.

(13) Any person who is otherwise eligible to possess a firearm under this chapter and who is operating a motor vehicle which is registered in the person's name or the name of a spouse or parent and which contains a firearm for which a valid license has been issued pursuant to section 6109 to the spouse or parent owning the firearm.

(14) A person lawfully engaged in the interstate transportation of a firearm as defined under 18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(3) (relating to definitions) in compliance with 18 U.S.C. § 926A (relating to interstate transportation of firearms).

(15) Any person who possesses a valid and lawfully issued license or permit to carry a firearm which has been issued under the laws of another state, regardless of whether a reciprocity agreement exists between the Commonwealth and the state under section 6109(k), provided:

(i) The state provides a reciprocal privilege for individuals licensed to carry firearms under section 6109.

(ii) The Attorney General has determined that the firearm laws of the state are similar to the firearm laws of this Commonwealth.

(16) Any person holding a license in accordance with section 6109(f)(3).

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6106

Long guns must remain unloaded in vehicles regardless of license.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6106.1

Definition of Loaded

"Loaded." A firearm is loaded if the firing chamber, the nondetachable magazine or, in the case of a revolver, any of the chambers of the cylinder contain ammunition capable of being fired. In the case of a firearm which utilizes a detachable magazine, the term shall mean a magazine suitable for use in said firearm which magazine contains such ammunition and has been inserted in the firearm or is in the same container or, where the container has multiple compartments, the same compartment thereof as the firearm. If the magazine is inserted into a pouch, holder, holster or other protective device that provides for a complete and secure enclosure of the ammunition, then the pouch, holder, holster or other protective device shall be deemed to be a separate compartment.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6102

Strict interpretation of “direct route” requirement under § 6106(b) exceptions. Com. v. McKown, 79 A.3d 678 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2013)

Storage Requirements

Some states have laws that require gun owners to take specific measures to secure their firearms, especially in households with children. Many of these state laws mandate that guns be stored in locked containers or safes when not in use. These laws often impose penalties for failing to secure firearms, particularly if they are accessed by unauthorized individuals, such as minors.

Other Weapons Restrictions

Lost or Stolen Firearms:

- Some municipalities, such as Philadelphia, have enacted lost/stolen reporting ordinances: Philadelphia Code § 10-838a requires reporting within 24 hours.

Police Encounter Laws

Some states impose a legal duty upon permit holders that requires them to inform a police officer of the presence of a firearm whenever they have an official encounter, such as a traffic stop. These states are called “duty to inform” states. In these states you are required by law to immediately, and affirmatively, tell a police officer if you have a firearm in your possession.

In addition to “duty to inform states,” some states have “quasi duty to inform” laws. These laws generally require that a permit holder have his/her permit in their possession and surrender it upon the request of an officer. The specific requirements of these laws will vary from state to state.

The final category of states is classified as “no duty to inform” states. In these states there are no laws that require a gun owner to affirmatively inform an officer if they have a firearm. Additionally, there are also generally no laws that require you to respond or provide a permit if asked about the presence of a firearm.

PA Stop and Identify (Terry Stop) Law:

-

- A person who refuses to provide identification upon demand of an officer whose duty it is to enforce this title after having been told by the officer that the person is the subject of an official investigation or investigative detention, supported by reasonable suspicion, commits a summary offense of the fifth degree.

- A person who provides false identification to an officer whose duty it is to enforce this title for the purpose of avoiding prosecution or hindering apprehension or obstructing an investigation commits a summary offense of the second degree.

34 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 904

Proof of license and exception.

(a) General rule.--When carrying a firearm concealed on or about one's person or in a vehicle, an individual licensed to carry a firearm shall, upon lawful demand of a law enforcement officer, produce the license for inspection. Failure to produce such license either at the time of arrest or at the preliminary hearing shall create a rebuttable presumption of nonlicensure.

(b) Exception.--An individual carrying a firearm on or about his person or in a vehicle and claiming an exception under section 6106(b) (relating to firearms not to be carried without a license) shall, upon lawful demand of a law enforcement officer, produce satisfactory evidence of qualification for exception.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 6122

Com. v. Hicks, 208 A.3d 916 (Pa. 2019)

Red Flag or Emergency Risk Orders

Emergency Risk Orders (or "Red Flag Laws") enable rapid legal action when someone is believed to be at significant risk of harming themselves or others with a firearm. Generally speaking, these controversial laws allow law enforcement to seek a court order to temporarily confiscate firearms from the individual and prevent them from purchasing new ones while the order is in effect. The most robust laws also permit family members and others to file petitions.

Use of Force in Defense of Person

The legal use of force, including deadly force, is regulated by state law. There are no federal laws that dictate when you can use force in self-defense in all states. As such, it is essential to become familiar with individual state laws.

Use of force justifiable for protection of the person.

The use of force upon or toward another person is justifiable when the actor believes that such force is immediately necessary for the purpose of protecting himself against the use of unlawful force by such other person on the present occasion.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 505 (a)

Justification Generally

(a) General rule.--Conduct which the actor believes to be necessary to avoid a harm or evil to himself or to another is justifiable if:

- (1) the harm or evil sought to be avoided by such conduct is greater than that sought to be prevented by the law defining the offense charged;

- (2) neither this title nor other law defining the offense provides exceptions or defenses dealing with the specific situation involved; and

- (3) a legislative purpose to exclude the justification claimed does not otherwise plainly appear.

(b) Choice of evils.--When the actor was reckless or negligent in bringing about the situation requiring a choice of harms or evils or in appraising the necessity for his conduct, the justification afforded by this section is unavailable in a prosecution for any offense for which recklessness or negligence, as the case may be, suffices to establish culpability.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 503

Use of Force in Defense of Others

Defense of third party laws allow an individual to use force, including deadly force, to protect another person from harm. These laws generally permit intervention if the third party would have had the right to use force in their own self-defense under the same circumstances. The exact application of these laws will vary by jurisdiction, so it is important to understand the framework of each individual state.

The use of force upon or toward the person of another is justifiable to protect a third person when:

- The actor would be justified in using such force to protect himself against the injury he believes to be threatened to the person whom he seeks to protect.

- Under the circumstances as the actor believes them to be, the person whom he seeks to protect would be justified in using such protective force,

- The actor believes that his intervention is necessary for the protection of such other persons.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 506

Use of Force in Defense of Habitation

The term "castle doctrine" comes from English common law providing that one's abode is a special area in which one enjoys certain protections and immunities, from which one is not obligated to retreat before defending oneself against attack, and in which one may do so without fear of prosecution.

Many states have instituted castle doctrine laws, with varying degrees of formality. Some states have statutorily enacted castle doctrine laws, some have judicially-created protections (called “common laws”), while others have no amplified protections in the home at all.

Pennsylvania law:

You are presumed to have a reasonable belief that deadly force is immediately necessary to protect yourself against death, serious bodily injury, kidnapping or sexual intercourse compelled by force or threat if both of the following conditions exist:

- The person against whom the force is used is in the process of unlawfully and forcefully entering, or has unlawfully and forcefully entered and is present within, a dwelling, residence or occupied vehicle; or the person against whom the force is used is or is attempting to unlawfully and forcefully remove another against that other's will from the dwelling, residence or occupied vehicle; and

- The actor knows or has reason to believe that the unlawful and forceful entry or act is occurring or has occurred.

*This presumption does not apply if the intruder: (1) has a right to be in the dwelling or vehicle, (2) the person being removed is a child or grandchild of the person removing them, (3) you are engaged in criminal activity, or (4) the intruder is a police officer doing his duty.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 505 (b)(2.1 & 2.5)

Deadly force is only justified for the purpose of protecting property in a dwelling if:

- there has been an entry into the actor's dwelling;

- the actor neither believes nor has reason to believe that the entry is lawful; and

- the actor neither believes nor has reason to believe that force less than deadly force would be adequate to terminate the entry.

OR

- the person against whom the force is used is attempting to dispossess him of his dwelling otherwise than under a claim of right to its possession; or

- such force is necessary to prevent the commission of a felony in the dwelling.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 507(c)(4)(e)

Case Law:

Clarified that the presumption is rebuttable if evidence suggests the defender’s belief was unreasonable. Commonwealth v. Childs, 142 A.3d 823 (Pa. 2016)

Force must still be proportionate; Castle Doctrine is not a license to kill in all home entry cases. Commonwealth v. Cannavo, 199 A.3d 1282 (Pa. 2018)

*Note: There are ongoing debates in the PA legislature about whether to extend Castle Doctrine presumptions to curtilage (yard, porch, garage).

Use of Force in Defense of Property

Generally speaking, the use of deadly force is limited to circumstances that reasonably present an imminent threat of serious bodily injury or death of a human being. As such, using deadly force in defense of mere personal property is almost categorically prohibited. Although most states will allow the use of some amount of force (i.e. physically restraining someone until the police arrive), the use or threatened use of deadly force in defense of mere property is generally not permitted.

Use of force for the protection of property.

- Use of force justifiable for protection of property.--The use of force upon or toward the person of another is justifiable when the actor believes that such force is immediately necessary:

- to prevent or terminate an unlawful entry or other trespass upon land or a trespass against or the unlawful carrying away of tangible movable property, if such land or movable property is, or is believed by the actor to be, in his possession or in the possession of another person for whose protection he acts; or

- to effect an entry or reentry upon land or to retake tangible movable property, if:

- the actor believes that he or the person by whose authority he acts or a person from whom he or such other person derives title was unlawfully dispossessed of such land or movable property and is entitled to possession; and

- -

- the force is used immediately or on fresh pursuit after such dispossession; or

- the actor believes that the person against whom he uses force has no claim of right to the possession of the property and, in the case of land, the circumstances, as the actor believes them to be, are of such urgency that it would be an exceptional hardship to postpone the entry or reentry until a court order is obtained.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § §507(a)

Arrest by Private Person:

Arrest without warrant.

(a) General rule.--For any of the following offenses, a police officer shall, upon view, have the right of arrest without warrant upon probable cause when there is ongoing conduct that imperils the personal security of any person or endangers public or private property:

(1) Under Title 18 (relating to crimes and offenses) when such offense constitutes a summary offense:

18 Pa.C.S. § 5503 (relating to disorderly conduct).

18 Pa.C.S. § 5505 (relating to public drunkenness).

18 Pa.C.S. § 5507 (relating to obstructing highways and other public passages).

18 Pa.C.S. § 6308 (relating to purchase, consumption, possession or transportation of liquor or malt or brewed beverages).

(2) Violation of an ordinance of a city of the second class.

(b) Guidelines by governmental body.--The right of arrest without warrant under this section shall be permitted only after the governmental body employing the police officer promulgates guidelines to be followed by a police officer when making a warrantless arrest under this section.

42 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 8902

Case Law:

Emphasized that property alone is not worth deadly force; must be tied to preventing serious harm. Commonwealth v. Capitolo, 498 A.2d 806 (Pa. 1985)

A deadly response to minor theft was unjustified. Commonwealth v. Mayfield, 585 A.2d 1069 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1991)

Civilian arrests are narrowly construed; unnecessary force invalidates justification. Commonwealth v. Chermansky, 552 A.2d 1128 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1989)

*Proposed 2025 amendments to § 507 would add explicit protections for defending business property after hours if intrusion is forceful and at night.

Self-Defense Immunity

To address the risk that those acting in lawful self-defense might be sued by their attacker, some states have implemented protective measures in the form of civil immunity statutes. These statutes serve to shield victims from certain civil lawsuits. If a state has a civil immunity statute in place, you generally enjoy protection from being sued by your attacker or attacker’s family as long as your use of force is deemed to be criminally justified. This legal framework provides a layer of protection for individuals who, in the course of defending themselves, might otherwise be subjected to additional legal challenges in the form of civil lawsuits.

(a) General rule.--An actor who uses force:

- (1) in self-protection as provided in 18 Pa.C.S. § 505 (relating to use of force in self-protection);

- (2) in the protection of other persons as provided in 18 Pa.C.S. § 506 (relating to use of force for the protection of other persons);

- (3) for the protection of property as provided in 18 Pa.C.S. § 507 (relating to use of force for the protection of property);

- (4) in law enforcement as provided in 18 Pa.C.S. § 508 (relating to use of force in law enforcement); or

- (5) consistent with the actor's special responsibility for care, discipline or safety of others as provided in 18 Pa.C.S. § 509 (relating to use of force by persons with special responsibility for care, discipline or safety of others) is justified in using such force and shall be immune from civil liability for personal injuries sustained by a perpetrator which were caused by the acts or omissions of the actor as a result of the use of force.

(b) Attorney fees and costs. If the actor who satisfies the requirements of subsection (a) prevails in a civil action initiated by or on behalf of a perpetrator against the actor, the court shall award reasonable expenses to the actor. Reasonable expenses shall include, but not be limited to, attorney fees, expert witness fees, court costs and compensation for loss of income.

42 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 8340.2

Reaffirmed that self-defense justification is a threshold issue; if proven, the case may be dismissed pretrial. Commonwealth v. Childs, 142 A.3d 823 (Pa. 2016)

Duty to Retreat

A duty to retreat is an obligation to flee that is imposed upon a civilian who is under attack. If applicable, it applies to the victim of unlawful force prior to their ability to use deadly force to defend him or herself. The duty to retreat makes self-defense unavailable to those who use deadly force when they could have retreated from the confrontation safely. The alternative to duty-to-retreat laws is no-duty-to-retreat laws or stand-your-ground laws as they’re commonly called. Stand-your-ground states impose no duty to flee upon victims and instead state that one can stand their ground and meet force with force, under certain situations.

2.3 An actor who is not engaged in a criminal activity, who is not in illegal possession of a firearm and who is attacked in any place where the actor would have a duty to retreat under paragraph (2)(ii) has no duty to retreat and has the right to stand his ground and use force, including deadly force, if:

- the actor has a right to be in the place where he was attacked;

- the actor believes it is immediately necessary to do so to protect himself against death, serious bodily injury, kidnapping or sexual intercourse by force or threat; and

- the person against whom the force is used displays or otherwise uses:

- a firearm or replica of a firearm as defined in 42 Pa.C.S. § 9712 (relating to sentences for offenses committed with firearms); or

- any other weapon readily or apparently capable of lethal use.

2.4 The exception to the duty to retreat set forth under paragraph (2.3) does not apply if the person against whom the force is used is a peace officer acting in the performance of his official duties and the actor using force knew or reasonably should have known that the person was a peace officer.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 505 (b) (2.3) & (2.4)

Conduct sufficient to excite an intense passion in a reasonable person.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 2301

Case Law:

If safe retreat is possible and deadly force is used, justification is lost. Commonwealth v. Mayfield, 585 A.2d 1069 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1991)

Clarified no duty to retreat in public if “stand your ground” conditions are met. Commonwealth v. Mouzon, 53 A.3d 738 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2012)

Mutual combat situations where the actor did not clearly withdraw. Commonwealth v. Fowlin, 710 A.2d 1130 (Pa. 1998)

Self-Defense Limitations

Limitations on justifying necessity for use of force.

(1) The use of force is not justifiable under this section:

-

- to resist an arrest which the actor knows is being made by a peace officer, although the arrest is unlawful; or

- to resist force used by the occupier or possessor of property or by another person on his behalf, where the actor knows that the person using the force is doing so under a claim of right to protect the property, except that this limitation shall not apply if:

- the actor is a public officer acting in the performance of his duties or a person lawfully assisting him therein or a person making or assisting in a lawful arrest;

- the actor has been unlawfully dispossessed of the property and is making a reentry or recaption justified by section 507 of this title (relating to use of force for the protection of property); or

- the actor believes that such force is necessary to protect himself against death or serious bodily injury.

(2) The use of deadly force is not justifiable under this section unless the actor believes that such force is necessary to protect himself against death, serious bodily injury, kidnapping or sexual intercourse compelled by force or threat; nor is it justifiable if:

-

-

-

- the actor, with the intent of causing death or serious bodily injury, provoked the use of force against himself in the same encounter; or

- the actor knows that he can avoid the necessity of using such force with complete safety by retreating, except the actor is not obliged to retreat from his dwelling or place of work, unless he was the initial aggressor or is assailed in his place of work by another person whose place of work the actor knows it to be.

-

-

(2.1) Except as otherwise provided in paragraph (2.2), an actor is presumed to have a reasonable belief that deadly force is immediately necessary to protect himself against death, serious bodily injury, kidnapping or sexual intercourse compelled by force or threat if both of the following conditions exist:

- The person against whom the force is used is in the process of unlawfully and forcefully entering, or has unlawfully and forcefully entered and is present within, a dwelling, residence or occupied vehicle; or the person against whom the force is used is or is attempting to unlawfully and forcefully remove another against that other's will from the dwelling, residence or occupied vehicle.

- The actor knows or has reason to believe that the unlawful and forceful entry or act is occurring or has occurred.

(2.2) The presumption set forth in paragraph (2.1) does not apply if:

- the person against whom the force is used has the right to be in or is a lawful resident of the dwelling, residence or vehicle, such as an owner or lessee;

- the person sought to be removed is a child or grandchild or is otherwise in the lawful custody or under the lawful guardianship of the person against whom the protective force is used;

- the actor is engaged in a criminal activity or is using the dwelling, residence or occupied vehicle to further a criminal activity; or

- the person against whom the force is used is a peace officer acting in the performance of his official duties and the actor using force knew or reasonably should have known that the person was a peace officer.

18 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 505 (b)

Use of Force Considerations

COMING SOON!

Use of Force Against Animals

A person may kill a dog that is in the act of pursuing, wounding, or killing any domestic animal; wounding or killing other dogs, cats, or household pets; or pursuing, wounding or attacking human beings, whether or not the dog bears a license tag. A person is not liable for damages for such a killing

3 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. §§ 459, 501, 531, and 532

In Pennsylvania, it is unlawful to kill any game animal or wildlife as a means of protection, unless it is clearly evident from all the facts that a human is endangered to the degree that the immediate destruction of the game or wildlife is necessary.

34 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 2141

Cases to Watch

COMING SOON!

Latest Updates

07/02/2025 Update:

- Reciprocity Update: A Memorandum of Agreement was signed on June 11, 2025, by Pennsylvania Attorney General Dave Sunday and Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares, restoring mutual recognition of each state’s License to Carry Firearms (LTC) for concealed handgun carry in the other state. The agreement is only applicable to handguns and requires permit holders to:

- Be at least 21 years of age

- Carry photo identification

- Display the concealed carry permit when asked by law enforcement

- Not have a concealed carry permit previously revoked

08/14/2025 Update:

- *PENDING Crimes and Offenses and Domestic Relations (HB454): An Act amending Titles 18 (Crimes and Offenses) and 23 (Domestic Relations) of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes, in firearms and other dangerous articles, repealing provisions relating to firearms not to be carried without a license, providing for license not required, repealing provisions relating to carrying firearms on public streets or public property in Philadelphia, further providing for prohibited conduct during emergency, providing for sportsman's firearm permit, further providing for licenses and for antique firearms and repealing provisions relating to proof of license and exception; and making editorial changes.