Quick Reference

Magazine Capacity Restrictions

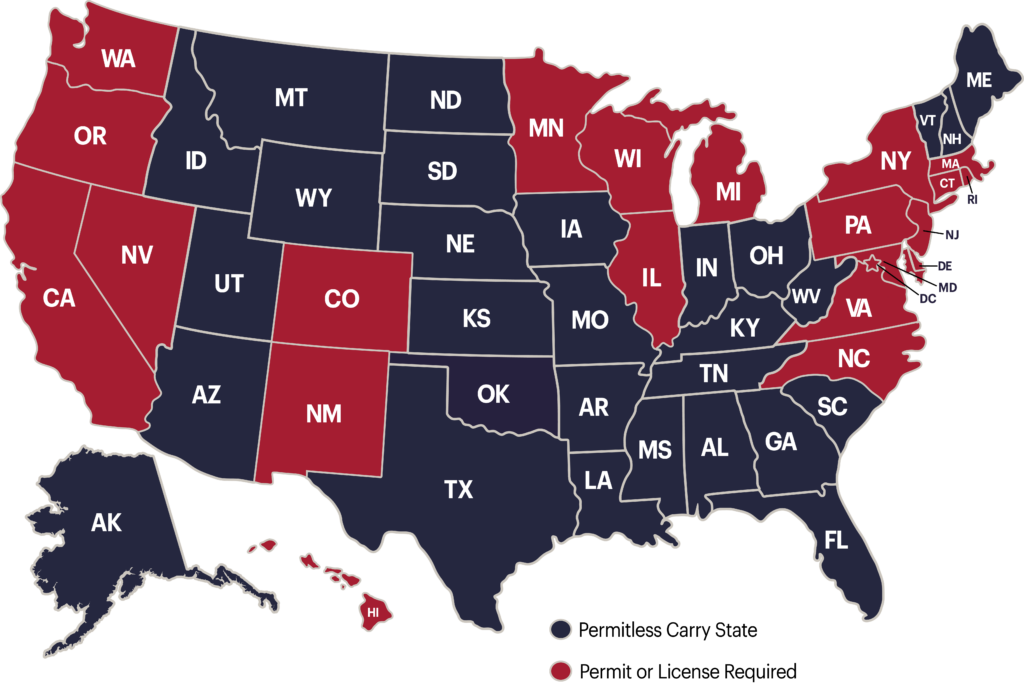

Constitutional (Permitless) Carry Allowed

Red Flag Laws

Carry in Alcohol Establishments Allowed

Open Carry Allowed

No Weapons Signs Enforced by Law

NFA Weapons Allowed

Duty to Retreat

Duty to Inform Law Enforcement

"Universal" Background Checks Required

Table of Contents

State Law Summary

Constitution of the State of Idaho - Article I, Section 11

“The people shall have the right to bear arms."

Idaho's firearm law history reflects a gradual evolution toward more permissive gun rights, marked by significant legal cases and legislative changes. In 1990, the Idaho Legislature passed the "Idaho Firearm Freedom Act," asserting the state's authority to regulate firearms made and retained within its borders, a move later challenged in courts but emblematic of state-level resistance to federal gun regulations. The landmark case of State v. Hunsaker (1999) reinforced individual rights to carry firearms openly. In 2016, Idaho adopted constitutional carry, allowing individuals aged 18 and older to carry concealed firearms without a permit, which further expanded gun rights in the state. Additionally, Idaho has consistently upheld its commitment to the Second Amendment, with laws allowing for firearms in certain public places, including schools, showcasing a trend toward bolstering individual rights in firearm ownership and carry.

Permit Eligibility, Training and Application Process

Idaho's history of concealed carry has evolved significantly over the years, with key legislative milestones shaping its current framework. In 1990, Idaho passed its first concealed carry law, requiring a permit for carrying a concealed weapon. The law underwent several amendments, and in 2006, Idaho introduced "shall issue" permitting, mandating that authorities grant permits to applicants who met the legal requirements. A notable change occurred in 2014 when the state enacted a law allowing concealed carry without a permit for individuals aged 18 and older. This move further expanded gun rights in Idaho, reflecting a growing trend toward permissive concealed carry laws across the U.S.

Idaho License Eligibility A license to carry concealed weapons shall not be issued to any person who:

- Is under twenty-one (21) years of age, except as otherwise provided in this section;

- Is formally charged with a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one (1) year;

- Has been adjudicated guilty in any court of a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one (1) year;

- Is a fugitive from justice;

- Is an unlawful user of marijuana or any depressant, stimulant or narcotic drug, or any controlled substance as defined in 21 U.S.C. section 802;

- Is currently suffering from or has been adjudicated as having suffered from any of the following conditions, based on substantial evidence: Lacking mental capacity;

- Mentally ill; Gravely disabled; An incapacitated person

- Has been discharged from the armed forces under dishonorable conditions;

- Has received a withheld judgment or suspended sentence for a crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one (1) year, unless the person has successfully completed probation;

- Has received a period of probation after having been adjudicated guilty of, or received a withheld judgment for, a misdemeanor offense that has as an element the intentional use, attempted use or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another, unless the person has successfully completed probation;

- Is an alien illegally in the United States;

- Is a person who having been a citizen of the United States has renounced his or her citizenship;

- Is free on bond or personal recognizance pending trial, appeal or sentencing for a crime which would disqualify him from obtaining a concealed weapons license;

- Is subject to a protection order issued under chapter 63, title 39, Idaho Code, that restrains the person from harassing, stalking or threatening an intimate partner of the person or child of the intimate partner or person, or engaging in other conduct that would place an intimate partner in reasonable fear of bodily injury to the partner or child; or

- Is for any other reason ineligible to own, possess or receive a firearm under the provisions of Idaho or federal law.

Idaho Code § 18-3302(11)(a-n)

Idaho CWL Training Requirements The sheriff may require the applicant to demonstrate familiarity with a firearm and must accept any one (1) of the following as evidence of the applicant's familiarity with a firearm:

- Completion of any hunter education or hunter safety course approved by the department of fish and game or a similar agency of another state;

- Completion of any national rifle association firearms safety or training course or any national rifle association hunter education course or any equivalent course;

- Completion of any firearms safety or training course or class available to the general public offered by a law enforcement agency, community college, college, university or private or public institution or organization or firearms training school, utilizing instructors certified by the national rifle association or the Idaho state police;

- Completion of any law enforcement firearms safety or training course or class offered for security guards, investigators, special deputies, or offered for any division or subdivision of a law enforcement agency or security enforcement agency;

- Evidence of equivalent experience with a firearm through participation in organized shooting competition or military service;

- A current license to carry concealed weapons pursuant to this section, unless the license has been revoked for cause;

- Completion of any firearms training or safety course or class conducted by a state-certified or national rifle association-certified firearms instructor; or

- Other training that the sheriff deems appropriate.

Idaho Code § 18-3302(9)

Idaho ECWL Training Requirements Applicants for an Enhanced CWL must complete a course which meets the following requirements:

- The course instructor is certified by the national rifle association, or by another nationally recognized organization that customarily certifies firearms instructors, as an instructor in personal protection with handguns, or the course instructor is certified by the Idaho peace officers standards and training council as a firearms instructor;

- The course is at least eight (8) hours in duration;

- The course is taught face to face and not by electronic or other means; and

- The course includes instruction in:

Idaho law relating to firearms and the use of deadly force, provided that such instruction is delivered by either of the following whose name and credential must appear on the certificate:

- An active, senior or emeritus member of the Idaho state bar; or

- A law enforcement officer who possesses an intermediate or higher Idaho peace officers standards and training certificate;

- The basic concepts of the safe and responsible use of handguns;

- Self-defense principles; and

- Live fire training including the firing of at least ninety-eight (98) rounds by the student.An instructor must provide a copy of the syllabus and a written description of the course of fire used in a qualifying handgun course that includes the name of the individual instructing the legal portion of the course to the sheriff upon request.

Idaho Code § 18-3302K(4)(c)

Idaho Provisional CWL The sheriff of a county shall issue a license to carry a concealed weapon to those individuals between the ages of eighteen (18) and twenty-one (21) years who, except for the age requirement contained in section 18-3302K(4), Idaho Code, would otherwise meet the requirements for issuance of a license under section 18-3302K, Idaho Code. Licenses issued to individuals between the ages of eighteen (18) and twenty-one (21) years under this subsection shall be easily distinguishable from licenses issued pursuant to subsection (7) of this section. A license issued pursuant to this subsection after July 1, 2016, shall expire on the twenty-first birthday of the licensee. A licensee, upon attaining the age of twenty-one (21) years, shall be allowed to renew the license under the procedure contained in section 18-3302K(9), Idaho Code. Such renewal license shall be issued as an enhanced license pursuant to the provisions of section 18-3302K, Idaho Code.

Idaho Code § 18-3302(20)

Idaho License Application Process Applicants for a CWL or Enhanced CWL must do the following:

- Apply in person at the county sheriff’s office

- Provide proof of completion of the required training

- Submit fingerprints with the application

- Pay a $20 application fee (the sheriff may add additional fees necessary to cover the cost of processing fingerprints or necessary materials)

The sheriff’s office shall issue the CWL or Enhanced CWL within 90 days. The license shall be valid for 5 years from the date of issuance. The fee for renewal of the license shall be $15.

Idaho Code § 18-3302

Renewal Application Process:

Every license that is not, as provided by law, suspended, revoked or disqualified in this state shall be renewable at any time during the ninety (90) day period before its expiration or within ninety (90) days after the expiration date. The sheriff must mail renewal notices ninety (90) days prior to the expiration date of the license. The sheriff shall require the licensee applying for renewal to complete an application. The sheriff must submit the application to the Idaho state police for a records check of state and national databases.

The Idaho state police must conduct the records check and return the results to the sheriff within thirty (30) days. The sheriff shall not issue a renewal before receiving the results of the records check and must deny a license if the applicant is disqualified under any of the criteria provided in this section. A renewal license shall be valid for a period of five (5) years. A license so renewed shall take effect on the expiration date of the prior license. A licensee renewing ninety-one (91) days to one hundred eighty (180) days after the expiration date of the license must pay a late renewal penalty of ten dollars ($10.00) in addition to the renewal fee unless waived by the sheriff, except that any licensee serving on active duty in the armed forces of the United States during the renewal period shall not be required to pay a late renewal penalty upon renewing ninety-one (91) days to one hundred eighty (180) days after the expiration date of the license. After one hundred eighty-one (181) days, the licensee must submit an initial application for a license and pay the fees prescribed in subsection (15) of this section. The renewal fee and any penalty shall be paid to the sheriff for the purpose of enforcing the provisions of this chapter. Upon renewing a license under the provisions of this section, the sheriff must notify the Idaho state police within five (5) days on a form or in a manner prescribed by the Idaho state police.

Application Fees:

The fee for renewal of the license shall be fifteen dollars ($15.00), which the sheriff must retain for the purpose of performing the duties required in this section. The sheriff may collect the actual cost of any additional fees necessary to cover the processing costs lawfully required by any state or federal agency or department, and the actual cost of materials for the license lawfully required by any state agency or department, which costs must be paid to the state.

Where to Apply:

Applicants must apply in person at the county sheriff’s office. If the applicant chooses to, they may print out the application but not sign it until they go into the sheriff's office. The application can be printed out from this link:

https://isp.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/BCI/Reciprocity/Training/CWL-Application.pdf

What to Include with Application:

- A completed application

- $15 application fee

Idaho Code § 18-3302(17)

Idaho Code § 18-3302K(8-9)

Instructor Eligibility:

The classroom portion must be taught by an Idaho Peace Officer with an intermediate certificate or higher or by a member of the Idaho State Bar. This instructor must be listed on the class certificate;

The instructor also must have received their firearms training by an NRA school, POST course or something equivalent. However, an NRA-certified instructor may contract with someone meeting those other credentials (Idaho Peace Officer with an intermediate certificate or higher or by a member of the Idaho State Bar) to teach the classroom portion of the course;

- Must be at least 21 years of age;

- Must pass a background check; and must

- Obtain liability insurance.

Instructor Application Process:

There is no application process; however, an issuing Sheriff or their designee can require a copy of the instructor's training and course curriculum before they accept the training that an instructor has provided.

Instructors must show up in person at their local county sheriff’s office to show them a copy of their training and course curriculum.

It is recommended that the instructor call the local sheriff in their county because some sheriff’s offices take appointments only.

Also, the instructor must submit fingerprints along with a copy of their instructor’s training and course curriculum (fingerprints are provided by the local sheriff’s office) and pay a $20 background check fee (the sheriff may add additional fees necessary to cover the cost of processing fingerprints and necessary materials).

The 8-hour E-CWL Course is specific to Idaho law as part of the course dealing with the use of deadly force and must be taught by an Idaho licensed attorney or a certified Idaho peace officer. Instructor’s students are also required to shoot 98 rounds on a firearms range.

Application Fees:

$0 application fee, but $20 for fingerprints/background check fee payable to the local sheriff’s office for initial Firearm Instructor application.

What to Include with Application:

- A copy the instructor's training and course curriculum

- Fingerprints (they will be taken at the sheriff’s office)

- The $20 background check fee (for the fingerprints)

- A firearms training certificate (if required by their county sheriff’s office)

Where to Apply:

Instructors must show up in person at their local county sheriff’s office to show them a copy of their training and course curriculum. It is recommended that the instructor call the local sheriff in their county because some sheriff’s offices take appointments only.

Permitless Carry Law

The terms “constitutional carry” and “permitless carry” refer to states that have laws allowing individuals to carry a loaded firearm in public without requiring a license or permit.

Idaho Permitless Carry

First in 2016, and then expanded in 2020, the Idaho legislature passed a permitless concealed carry law. A person does not have to have a concealed weapons license to carry or be in possession of a deadly weapon or firearm in the following circumstances:

- Any deadly weapon located in plain view;

- Any lawfully possessed shotgun or rifle;

- Any deadly weapon concealed in a motor vehicle;

- A firearm that is not loaded and is secured in a case;

- A firearm that is disassembled or permanently altered such that it is not readily operable; and

- Any deadly weapon concealed by a person who:

- Is over eighteen (18) years of age;

- Is a citizen of the United States or a current member of the armed forces of the United States; and

- Is not disqualified from being issued a license under paragraphs (b) through (n) of subsection (11) of this section.

Idaho Code § 18-3302

Reciprocity Agreements

Reciprocity refers to an agreement between states to recognize, or honor, a concealed firearm permit issued by another state.

When you are in another state, you are subject to that state’s laws. Even if a state recognizes your carry permit or allows for permitless carry, the state may have additional restrictions on certain types of firearms, magazines, or ammunition. Take time to learn the law!

State Preemption Laws

State firearm preemption laws are statutes that prevent local governments from enacting or enforcing their own gun regulations that are more restrictive than state law. These laws ensure that firearm regulations remain consistent across the state, preventing a patchwork of different rules in various cities or counties.

Idaho Preemption Law

Idaho has a preemption law, which means only the state may enact firearm regulations.

- The legislature finds that uniform laws regulating firearms are necessary to protect the individual citizen's right to bear arms guaranteed by amendment 2 of the United States Constitution and section 11, article I of the constitution of the state of Idaho. It is the legislature's intent to wholly occupy the field of firearms regulation within this state.

- Except as expressly authorized by state statute, no county, city, agency, board or any other political subdivision of this state may adopt or enforce any law, rule, regulation, or ordinance which regulates in any manner the sale, acquisition, transfer, ownership, possession, transportation, carrying or storage of firearms or any element relating to firearms and components thereof, including ammunition.

Idaho Code § 18-3302J

Purchase/Transfer Laws

When buying or selling a firearm, both federal and state laws must be followed. Under 18 U.S.C. § 922(a)(5), a private party may sell a firearm to a resident of the same state if two conditions are met: (1) the seller and buyer must be residents of the same state, and (2) the seller must not know or have reasonable cause to believe that the buyer is prohibited from receiving or possessing firearms under federal law, as outlined in 18 U.S.C. § 922(g).

Additionally, a private seller may loan or rent a firearm to a resident of any state for temporary lawful sporting use, provided they meet the same condition of not knowing or having reason to believe the borrower is prohibited under federal law.

In addition to federal law, state laws governing firearm sales must also be followed, as states may impose additional restrictions such as background checks, waiting periods, or bans on specific types of firearms.

Idaho Private-Party Transfers

In Idaho, a private party may sell or give a firearm to anyone who resides in Idaho so long as they are of legal age and not otherwise prohibited from owning a firearm.

It shall be unlawful to directly or indirectly sell to any minor under the age of eighteen (18) years any weapon without the written consent of the parent or guardian of the minor. Any person violating the provisions of this section shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and shall be punished by a fine not in excess of one thousand dollars ($1,000), by imprisonment in the county jail for a term not in excess of six (6) months, or by both such fine and imprisonment. As used in this section, "weapon" shall mean any dirk, dirk knife, bowie knife, dagger, pistol, revolver or gun.

Idaho Code § 18-3302A

Idaho Firearm Possession by Minors

It shall be unlawful for any person under the age of eighteen (18) years to possess or have in possession any weapon, as defined in section 18-3302A, Idaho Code, unless he:

- Has the written permission of his parent or guardian to possess the weapon; or

- Is accompanied by his parent or guardian while he has the weapon in his possession.

Any minor under the age of twelve (12) years in possession of a weapon shall be accompanied by an adult.

Any person who violates the provisions of this section is guilty of a misdemeanor.

Idaho Code § 18-3302E

Magazine Capacity Restrictions

Magazine capacity laws are designed to limit the number of rounds a firearm's magazine can hold, typically restricting it to a certain number of cartridges (e.g., 10 rounds or fewer). Some state laws restrict the amount of rounds that may be placed in a magazine at any given time, while others prevent the mere possession of unloaded magazines capable of accepting more than a certain number of rounds.

Prohibited Areas - Where Firearms Are Prohibited Under State law

Carrying a firearm into a place where firearms are prohibited by state or federal law is a common way for gun owners to find themselves in legal trouble. These places are known as “prohibited areas,” and they can vary greatly from state to state. Below you will find the list of the places where firearms are prohibited under this state’s laws. Keep in mind, in addition to these state prohibited areas, federal law adds additional places where firearms are prohibited. See the federal law section for a list of federal prohibited areas.

Places Where Firearms Are Prohibited Under Idaho Law:

- Courthouses

- Juvenile and adult correctional facilities

- Public and private schools

Idaho Code §18-3302C (1)

Idaho Schools School Property Exception: The prohibition against possessing a firearm on school property (K-12) does not apply to:

- Any adult over eighteen (18) years of age and not enrolled in a public or private elementary or secondary school who has lawful possession of a firearm or other deadly or dangerous weapon, secured and locked in his vehicle in an unobtrusive, nonthreatening manner... A person who lawfully possesses a firearm or other deadly or dangerous weapon in a private vehicle while delivering minor children, students or school employees to and from school or a school activity.

Idaho Code § 18-3302D (4)

Idaho Colleges and Universities Those who possess an Idaho Enhanced Permit may carry their firearm onto public university or college campuses except within:

- a student dormitory or residence hall; or

- any building of a public entertainment facility, provided that proper signage is conspicuously posted at each point of public ingress to the facility notifying attendees of any restriction on the possession of firearms in the facility during the game or event.

A “public entertainment facility” means an arena, stadium, amphitheater, auditorium, theater or similar facility with a seating capacity of at least one thousand (1,000) persons.

Idaho Code § 18-3309

Idaho Criminal Trespass Law A person commits criminal trespass and is guilty of a misdemeanor when he enters or remains on the real property of another without permission, knowing or with reason to know that his presence is not permitted. A person has reason to know his presence is not permitted when, except under a landlord-tenant relationship, he fails to depart immediately from the real property of another after being notified by the owner or his agent to do so, or he returns without permission or invitation within one (1) year, unless a longer period of time is designated by the owner or his agent. In addition, a person has reason to know that his presence is not permitted on real property that meets any of the following descriptions:

- The property is reasonably associated with a residence or place of business;

- The property is cultivated;

- The property is fenced or otherwise enclosed in a manner that a reasonable person would recognize as delineating a private property boundary. Provided, however, if the property adjoins or is contained within public lands, the fence line adjacent to public land is posted with conspicuous "no trespassing" signs or bright orange or fluorescent paint at the corners of the fence adjoining public land and at all navigable streams, roads, gates and rights-of-way entering the private land from the public land, and is posted in a manner that a reasonable person would be put on notice that it is private land; or

- The property is unfenced and uncultivated but is posted with conspicuous "no trespassing" signs or bright orange or fluorescent paint at all property corners and boundaries where the property intersects navigable streams, roads, gates and rights-of-way entering the land, and is posted in a manner that a reasonable person would be put on notice that it is private land.

Idaho Code § 18-7008(2)(a)

Methods of Carry - Open Carry Laws

Open carry and concealed carry refer to two distinct methods of carrying firearms in public. Open carry involves visibly carrying a firearm, typically in a holster, where it is easily seen by others. Concealed carry, on the other hand, involves carrying a firearm in a hidden manner, such as under clothing, so that it is not visible to others.

Idaho Open Carry

Open carry is generally allowed in Idaho with or without a permit, in all areas of the state where concealed carry is allowed.

Idaho Permitless Carry

First in 2016, and then expanded in 2020, the Idaho legislature passed a permitless concealed carry law. A person does not have to have a concealed weapons license to carry or be in possession of a deadly weapon or firearm in the following circumstances:

- Any deadly weapon located in plain view;

- Any lawfully possessed shotgun or rifle;

- Any deadly weapon concealed in a motor vehicle;

- A firearm that is not loaded and is secured in a case;

- A firearm that is disassembled or permanently altered such that it is not readily operable; and

- Any deadly weapon concealed by a person who:

- Is over eighteen (18) years of age;

- Is a citizen of the United States or a current member of the armed forces of the United States; and

- Is not disqualified from being issued a license under paragraphs (b) through (n) of subsection (11) of this section.

Idaho Code § 18-3302

Exhibition or Use of a Deadly Weapon

Every person who, not in necessary self-defense, in the presence of two (2) or more persons, draws or exhibits any deadly weapon in a rude, angry and threatening manner, or who, in any manner, unlawfully uses the same, in any fight or quarrel, is guilty of a misdemeanor.

Idaho Code § 18-3303

No Weapons Signs

No weapons" signs are notices posted by businesses or private property owners indicating that firearms or other weapons are not allowed on the premises. The legal impact of these signs varies by state. In some states, these signs have the force of law, meaning that if a person carries a weapon onto the property in violation of the sign, they can face criminal penalties such as fines or arrest. In these states, ignoring a "no weapons" sign can result in legal consequences similar to trespassing.

In other states, however, these signs are merely a business's policy, and while a person carrying a weapon might be asked to leave, there are no legal penalties for entering with a weapon unless they refuse to leave when asked, at which point trespassing laws may apply.

Controlled Substance/Alcohol Laws

Most, but not all, states have laws in place that regulate possessing firearms while intoxicated, and individual states will define "intoxicated" differently. In addition to state law, federal law also prohibits the possession of a firearm by any person who is “an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance” as defined by the Controlled Substances Act (“CSA”). There are five different schedules of controlled substances regulated by the CSA, scheduled as I–V. The types of drugs that are regulated range from heroin as a Schedule I substance, to Robitussin AC as a Schedule V substance. Even a gun owner that is prescribed a scheduled drug by a physician can be in legal jeopardy if it is proven that the drug was taken in a frequency or manner other than was prescribed. Although legal for medicinal or recreational use in many states, marijuana remains classified as a scheduled controlled substance under the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA), codified as 21 U.S.C. § 812. On May 16, 2024, the U.S. Department of Justice published a proposed rule change that would reclassify marijuana from schedule I to a schedule III drug. It is anticipated this rescheduling will formally occur in 2024 or 2025. Unlike schedule I drugs, schedule III drugs may be lawfully prescribed by a licensed physician, and thus the possession of these prescribed drugs does not make the possession of a firearm inherently unlawful the way possession of a schedule I substance would. This means that the rescheduling of marijuana to a schedule III drug would finally allow for the lawful use, possession and purchase of firearms by prescription marijuana users. However, if it is determined that the marijuana is possessed without a prescription, is used in a manner that is not prescribed, or that the individual with the prescription is addicted to marijuana, possession of a firearm would still be a federal offense. Federal law states that a person is addicted to a controlled substance when they have “lost the power of self-control with reference to the use of controlled substance; and any person who is a current user of a controlled substance in a manner other than as prescribed by a licensed physician.” 27 C.F.R. § 478.11, 18 U.S.C. §922(g)(3)

Consumption of Alcohol

- It shall be unlawful for any person to carry a concealed weapon on or about his person when intoxicated or under the influence of an intoxicating drink or drug. Any violation of the provisions of this section shall be a misdemeanor.

- In addition to any other penalty, any person who enters a plea of guilty, who is found guilty or who is convicted of a violation of subsection (1) of this section when such violation occurs on a college or university campus shall have any and all licenses issued pursuant to section 18-3302, 18-3302H or 18-3302K, Idaho Code, revoked for a period of three (3) years and such person shall be ineligible to obtain or renew any such license or use any other license recognized by this state for the same period.

Idaho Code § 18-3302B

Vehicle and Transport Laws

Permit reciprocity and other differences between state regulation of firearms can create a difficult landscape for firearm owners to navigate while transporting firearms interstate. In 1968, and again in 1986, Congress set out to help hunters, travelers, and other firearm owners who were getting arrested for merely transporting firearms through restrictive states. To help simplify the complex web of state firearm laws, Congress passed the 1986 Firearm Owners Protection Act (“FOPA”) as part of Senate Bill 2414. The specific “safe harbor” provision of the law, often referred to as the “McClure-Volkmer Rule,” provides some protection for gun owners transporting firearms through restrictive states, subject to strict requirements. This federal law is covered in more detail in the federal law section of this database. Beyond federal law, the laws of each state will impose additional restrictions, or protections, related to transporting firearms in a vehicle.

Idaho Transporting a Firearm in a Vehicle Subsection (3) of this section shall not apply to restrict or prohibit the carrying or possession of:

- Any deadly weapon located in plain view;

- Any lawfully possessed shotgun or rifle;

- Any deadly weapon concealed in a motor vehicle;

- A firearm that is not loaded and is secured in a case;

- A firearm that is disassembled or permanently altered such that it is not readily operable; and

- Any deadly weapon concealed by a person who :

- Is over eighteen (18) years of age;

- Is a citizen of the United States or a current member of the armed forces of the United States; and

- Is not disqualified from being issued a license under paragraphs (b) through (n) of subsection (11) of this section.

Idaho Code § 18-3302(4)

Storage Requirements

Some states have laws that require gun owners to take specific measures to secure their firearms, especially in households with children. Many of these state laws mandate that guns be stored in locked containers or safes when not in use. These laws often impose penalties for failing to secure firearms, particularly if they are accessed by unauthorized individuals, such as minors.

Other Weapons Restrictions

Police Encounter Laws

Some states impose a legal duty upon permit holders that requires them to inform a police officer of the presence of a firearm whenever they have an official encounter, such as a traffic stop. These states are called “duty to inform” states. In these states you are required by law to immediately, and affirmatively, tell a police officer if you have a firearm in your possession.

In addition to “duty to inform states,” some states have “quasi duty to inform” laws. These laws generally require that a permit holder have his/her permit in their possession and surrender it upon the request of an officer. The specific requirements of these laws will vary from state to state.

The final category of states is classified as “no duty to inform” states. In these states there are no laws that require a gun owner to affirmatively inform an officer if they have a firearm. Additionally, there are also generally no laws that require you to respond or provide a permit if asked about the presence of a firearm.

Interacting with Police

Idaho is a no-duty-to-inform state, which means you are under no legal obligation to affirmatively inform an officer of the presence of your firearm and may not be under a legal obligation to respond if asked by the officer.

- If you choose to inform an officer that you have a firearm, make sure you follow these rules:

Keep your hands visible at all times. - Comply fully with all instructions given by the officer.

- If you are asked if you have a firearm in your presence, it is recommended that you be completely truthful and cooperative.

- If asked, advise the officer of the location of the firearm.

- Do not reach for your firearm or other weapons unless instructed to do so.

Red Flag or Emergency Risk Orders

Emergency Risk Orders (or "Red Flag Laws") enable rapid legal action when someone is believed to be at significant risk of harming themselves or others with a firearm. Generally speaking, these controversial laws allow law enforcement to seek a court order to temporarily confiscate firearms from the individual and prevent them from purchasing new ones while the order is in effect. The most robust laws also permit family members and others to file petitions.

Use of Force in Defense of Person

The legal use of force, including deadly force, is regulated by state law. There are no federal laws that dictate when you can use force in self-defense in all states. As such, it is essential to become familiar with individual state laws.

Idaho Self-Defense Law Homicide is justifiable when committed by any person in any of the following cases:

- When resisting any attempt to murder any person, or to commit a felony, or to do some great bodily injury upon any person;

- When committed in defense of habitation, a place of business or employment, occupied vehicle, property or person, against one who manifestly intends or endeavors, by violence or surprise, to commit a felony, or against one who manifestly intends and endeavors, in a violent, riotous or tumultuous manner, to enter the habitation, place of business or employment or occupied vehicle of another for the purpose of offering violence to any person therein;

- When committed in the lawful defense of such person, or of a wife or husband, parent, child, master, mistress or servant of such person, when there is reasonable ground to apprehend a design to commit a felony or to do some great bodily injury, and imminent danger of such design being accomplished; but such person, or the person in whose behalf the defense was made, if he was the assailant or engaged in mortal combat, must really and in good faith have endeavored to decline any further struggle before the homicide was committed; or

- When necessarily committed in attempting, by lawful ways and means, to apprehend any person for any felony committed, or in lawfully suppressing any riot, or in lawfully keeping and preserving the peace.

Idaho Code § 18-4009 (1)

Idaho Self-Defense Jury Instruction A homicide is justifiable if the defendant was acting in self-defense. In order to find that the defendant acted in self-defense, all of the following conditions must be found to have been in existence at the time of the killing:

- The defendant must have believed that the defendant was in imminent danger of death or great bodily harm.

- In addition to that belief, the defendant must have believed that the action the defendant took was necessary to save the defendant from the danger presented.

- The circumstances must have been such that a reasonable person, under similar circumstances, would have believed that the defendant was in imminent danger of death or great bodily injury and believed that the action taken was necessary.

- The defendant must have acted only in response to that danger and not for some other motivation.

Use of Force in Defense of Others

Defense of third party laws allow an individual to use force, including deadly force, to protect another person from harm. These laws generally permit intervention if the third party would have had the right to use force in their own self-defense under the same circumstances. The exact application of these laws will vary by jurisdiction, so it is important to understand the framework of each individual state.

Use of Force in Defense of Habitation

The term "castle doctrine" comes from English common law providing that one's abode is a special area in which one enjoys certain protections and immunities, from which one is not obligated to retreat before defending oneself against attack, and in which one may do so without fear of prosecution.

Many states have instituted castle doctrine laws, with varying degrees of formality. Some states have statutorily enacted castle doctrine laws, some have judicially-created protections (called “common laws”), while others have no amplified protections in the home at all.

Idaho “Castle Doctrine”

A person who unlawfully and by force or by stealth enters or attempts to enter a habitation… is presumed to be doing so with the intent to commit a felony.

Idaho Code § 18-4009 (2)

Deadly Force Presumption

A person using force or deadly force in defense of a habitation… is presumed to have acted reasonably and had a reasonable fear of imminent peril of death or serious bodily injury if the force is used against a person whose entry or attempted entry therein is unlawful and is made or attempted by use of force, or in a violent and tumultuous manner, or surreptitiously or by stealth, or for the purpose of committing a felony.

Idaho Code § 19-202A (5)

"Habitation" means any building, inhabitable structure or conveyance of any kind, whether the building, inhabitable structure or conveyance is temporary or permanent, mobile or immobile, including a tent, and is designed to be occupied by people lodging therein at night, and includes a dwelling in which a person resides either temporarily or permanently or is visiting as an invited guest, and includes the curtilage of any such dwelling.

Idaho Code § 18-4009 (3) (a)

Use of Force in Defense of Property

Generally speaking, the use of deadly force is limited to circumstances that reasonably present an imminent threat of serious bodily injury or death of a human being. As such, using deadly force in defense of mere personal property is almost categorically prohibited. Although most states will allow the use of some amount of force (i.e. physically restraining someone until the police arrive), the use or threatened use of deadly force in defense of mere property is generally not permitted.

Defense of Property

When conditions are present which under the law justify a person in using force in defense of [another] [the person] [the person’s family] [property in the person’s lawful possession], that person may use such degree and extent of force as would appear to be reasonably necessary to prevent the threatened injury.

Reasonableness is to be judged from the viewpoint of a reasonable person placed in the same position and seeing and knowing what the defendant then saw and knew. Any use of force beyond that limit is unjustified.

Idaho Criminal Jury Instruction 1522

Self-Defense Immunity

To address the risk that those acting in lawful self-defense might be sued by their attacker, some states have implemented protective measures in the form of civil immunity statutes. These statutes serve to shield victims from certain civil lawsuits. If a state has a civil immunity statute in place, you generally enjoy protection from being sued by your attacker or attacker’s family as long as your use of force is deemed to be criminally justified. This legal framework provides a layer of protection for individuals who, in the course of defending themselves, might otherwise be subjected to additional legal challenges in the form of civil lawsuits.

Idaho Civil Liability Law Any party maimed or wounded by the discharge of any firearm aforesaid, or the heirs or representatives of any person who may be killed by such discharge, may have an action against the party offending, for damages, which shall be found by a jury, and such damages, when found, may in the discretion of the court before which such action is brought, be doubled.

Idaho Code § 18-3307

Idaho Civil Immunity Law A person who uses force as justified [by the self-defense laws], is immune from any civil liability for the use of such force except when the person knew or reasonably should have known that the person against whom the force was used was a law enforcement officer acting in the capacity of his or her official duties.

Idaho Code § 6-808

Duty to Retreat

A duty to retreat is an obligation to flee that is imposed upon a civilian who is under attack. If applicable, it applies to the victim of unlawful force prior to their ability to use deadly force to defend him or herself. The duty to retreat makes self-defense unavailable to those who use deadly force when they could have retreated from the confrontation safely. The alternative to duty-to-retreat laws is no-duty-to-retreat laws or stand-your-ground laws as they’re commonly called. Stand-your-ground states impose no duty to flee upon victims and instead state that one can stand their ground and meet force with force, under certain situations.

Idaho Stand Your Ground Law

In the exercise of the right of self-defense or defense of another, a person need not retreat from any place that person has a right to be. A person may stand his ground and defend himself or another person by the use of all force and means which would appear to be necessary to a reasonable person in a similar situation and with similar knowledge without the benefit of hindsight. The provisions of this subsection shall not apply to a person incarcerated in jail or prison facilities when interacting with jail or prison staff who are acting in their official capacities.

Idaho Code § 19-202A (3)

Use of Force Against Animals

The killing of any animal, by any person at any time, which may be found outside of the owned or rented property of the owner or custodian of such animal, and which is found injuring or posing a threat to any person, farm animal or property.

[This] shall not be construed to be cruel nor shall [it] be defined as cruelty to animals, nor shall any person engaged in [this practice] be charged with cruelty to animals.

Idaho Code Ann. § 25-3514(6)

Cases to Watch

Manslaughter case:

State v. Custodio, Court of Appeals of Idaho. May 15, 2001, 136 Idaho 197

Defendant was convicted in the District Court of the Fourth Judicial District, Ada County, Joel D. Horton, J., of voluntary manslaughter, involuntary manslaughter, aggravated battery and burglary. Defendant appealed. The Court of Appeals, Perry, J., held that: (1) defendant knowingly and intelligently waived his Miranda rights; (2) trial court did not abuse its discretion in refusing to transfer venue due to pretrial publicity; (3) character evidence regarding victims was inadmissible; (4) trial court did not abuse its discretion in refusing to order a new trial based on newly discovered evidence; (5) sentencing enhancements for use of a deadly weapon in involuntary manslaughter and aggravated battery convictions were error; and (6) defendant's aggregate sentence was not excessive.

Custodio argues that contrary to the district court's analysis, the proper inquiry is not the number of crimes involved but whether those crimes arose out of the same indivisible course of conduct. The Idaho Supreme Court has addressed the scope of I.C. § 19–2520E in two previous cases. In State v. Searcy, 118 Idaho 632, 798 P.2d 914 (1990), the defendant hid in the back room of a store where he waited to either steal or rob as the situation dictated. Upon his discovery by the store owner, a confrontation ensued and the defendant shot the store owner in the stomach. The defendant then told the store owner that if she opened the safe he would call an ambulance. The store owner opened the safe and the defendant removed the money. The defendant then shot and killed the store owner. The defendant was convicted of robbery and murder, and the district court enhanced both sentences for use of a deadly weapon I.C. § 19–2520. However, pursuant to an I.C.R. 35 motion to correct an illegal sentence, the district court removed one of the enhancements after it determined that imposing both enhancements would violate the limitation contained in I.C. § 19–2520E. The Idaho Supreme Court stated that the district court's determination that the original sentence imposed on the defendant was invalid was correct because it contained two separate enhancements in violation of I.C. § 19–2520E. Searcy, 118 Idaho at 638, 798 P.2d at 920.

since possession of gun in local school zone was not economic activity that substantially affected interstate commerce.

Prohibited Areas case:U.S. v. Lopez, Supreme Court of the United States, April 26, 1995

Defendant was convicted in the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas, H.F. Garcia, J., of possessing firearm in school zone in violation of Gun-Free School Zones Act, and he appealed. The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Garwood, Circuit Judge, 2 F.3d 1342, reversed and remanded with directions, and government petitioned for certiorari review. After granting certiorari, 114 S. Ct. 1536, the United States Supreme Court, Chief Justice Rehnquist, held that Gun-Free School Zones Act, making it federal offense for any individual knowingly to possess firearm at place that individual knows or has reasonable cause to believe is school zone, exceeded Congress' commerce clause authority, since possession of gun in local school zone was not economic activity that substantially affected interstate commerce.

Latest Updates

08/05/2025 Update:

- An Act relating to concealed weapons (HB 48): Amending section 18-3302K, Idaho Code, to revise a provision regarding course instruction for an enhanced license to carry a concealed weapon and to make a technical correction; and declaring an emergency and providing an effective date.

Purpose is to maintain the ability of retired law enforcement officers to continue to instruct after they are no longer employed by a department. Currently after instructors retire, they are not legally able to continue teaching firearm safety and instruction on enhanced concealed carry certifications.

ID Code § 18-3302K

Signed by the governor on March 11, 2025. Effective date: July 1, 2025

10/21/2025 Update:

- Permit Eligibility, Training and Application Process section updated with content on Renewal Application Process, Instructor Eligibility, and Instructor Application Process.

- Cases to Watch section updated with content from a murder case and a prohibited areas case.

11/13/2025:

- Updated Use of Force Against Animals