Quick Reference

Magazine Capacity Restrictions

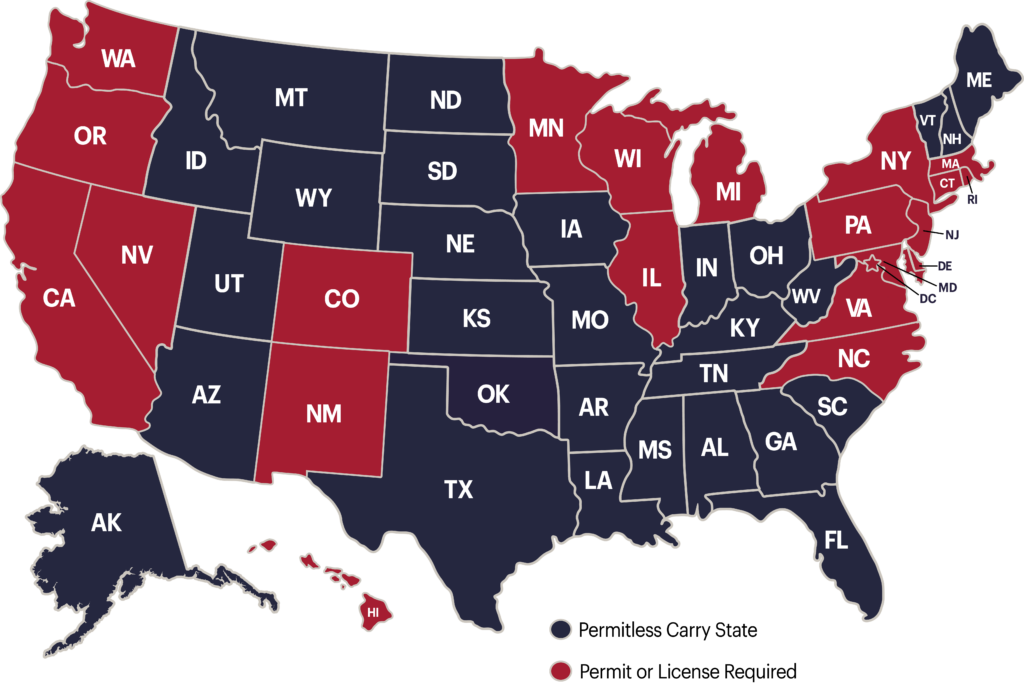

Constitutional (Permitless) Carry Allowed

Red Flag Laws

Carry in Alcohol Establishments Allowed

Open Carry Allowed

No Weapons Signs Enforced by Law

NFA Weapons Allowed

Duty to Retreat

Duty to Inform Law Enforcement

"Universal" Background Checks Required

Table of Contents

State Law Summary

Constitution of the State of Massachusetts - Part I, Art. XVII

"The people have a right to keep and bear arms for the common defense."

Massachusetts has a complex firearm law history marked by significant legal cases and legislative changes that reflect a balance between regulation and rights. The Gun Control Act of 1998 introduced a licensing system requiring firearm identification cards and permits for handguns, shaping the framework for gun ownership in the state. In 2004, the landmark case Commonwealth v. Smith reaffirmed the importance of due process in firearm license denials, emphasizing legal protections for applicants. The 2014 Act Relative to the Prevention of Gun Violence introduced further regulations, including restrictions on high-capacity magazines. More recently, the state has faced scrutiny over its strict laws, with discussions around the need for reform and better access to firearms for responsible citizens.

Permit Eligibility, Training and Application Process

The history of firearms licensing in Massachusetts has evolved significantly over the years, beginning with the Gun Control Act of 1968, which introduced the requirement for firearm identification cards. In 1998, the state implemented comprehensive reforms with the passing of the Gun Control Act, which mandated that individuals obtain a license to carry (LTC) for handguns and a firearm identification (FID) card for rifles and shotguns. This law established a more rigorous licensing process, including background checks and safety training. In 2004, the Commonwealth v. Smith case highlighted the need for due process in the licensing system, emphasizing the importance of fair treatment for applicants. The 2014 Act Relative to the Prevention of Gun Violence further tightened regulations, introducing measures such as mandatory reporting of lost or stolen firearms and restrictions on high-capacity magazines.

License Eligibility

A license shall not be issued to a prohibited person. A prohibited person shall be a person who:

- has, in a court of the commonwealth, been convicted or adjudicated a youthful offender or delinquent child, both as defined in section 52 of chapter 119, for the commission of (A) a felony; (B) a misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment for more than 2 years ; (C) a violent crime as defined in section 121; (D) a violation of any law regulating the use, possession, ownership, transfer, purchase, sale, lease, rental, receipt or transportation of weapons or ammunition for which a term of imprisonment may be imposed; (E) a violation of any law regulating the use, possession or sale of a controlled substance as defined in section 1 of chapter 94C including, but not limited to, a violation of said chapter 94C; or (F) a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence as defined in 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(33);

- has, in any other state or federal jurisdiction, been convicted or adjudicated a youthful offender or delinquent child for the commission of (A) a felony; (B) a misdemeanor punishable by imprisonment for more than 2 years; (C) a violent crime as defined in section 121; (D) a violation of any law regulating the use, possession, ownership, transfer, purchase, sale, lease, rental, receipt or transportation of weapons or ammunition for which a term of imprisonment may be imposed; (E) a violation of any law regulating the use, possession or sale of a controlled substance as defined in said section 1 of said chapter 94C including, but not limited to, a violation of said chapter 94C; or (F) a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence as defined in 18 U.S.C. 921(a)(33);

- is or has been (A) committed to a hospital or institution for mental illness, alcohol or substance abuse, except a commitment pursuant to sections 35 or 36C of chapter 123, unless after 5 years from the date of the confinement, the applicant submits with the application an affidavit of a licensed physician or clinical psychologist attesting that such physician or psychologist is familiar with the applicant's mental illness, alcohol or substance abuse and that in the physician's or psychologist's opinion, the applicant is not disabled by a mental illness, alcohol or substance abuse in a manner that shall prevent the applicant from possessing a firearm, rifle or shotgun; (B) committed by a court order to a hospital or institution for mental illness, unless the applicant was granted a petition for relief of the court order pursuant to said section 36C of said chapter 123 and submits a copy of the court order with the application; (C) subject to an order of the probate court appointing a guardian or conservator for a incapacitated person on the grounds that the applicant lacks the mental capacity to contract or manage the applicant's affairs, unless the applicant was granted a petition for relief of the order of the probate court pursuant to section 56C of chapter 215 and submits a copy of the order of the probate court with the application; or (D) found to be a person with an alcohol use disorder or substance use disorder or both and committed pursuant to said section 35 of said chapter 123, unless the applicant was granted a petition for relief of the court order pursuant to said section 35 and submits a copy of the court order with the application;

- is younger than 21 years of age at the time of the application;

- is an alien who does not maintain lawful permanent residency;

- is currently subject to: (A) an order for suspension or surrender issued pursuant to sections 3B or 3C of chapter 209A or a similar order issued by another jurisdiction; (B) a permanent or temporary protection order issued pursuant to said chapter 209A or a similar order issued by another jurisdiction, including any order described in 18 U.S.C. 922(g)(8); (C) a permanent or temporary harassment prevention order issued pursuant to chapter 258E or a similar order issued by another jurisdiction; or (D) an extreme risk protection order issued pursuant to sections 131R to 131X, inclusive, or a similar order issued by another jurisdiction.

- is currently the subject of an outstanding arrest warrant in any state or federal jurisdiction;

- has been discharged from the armed forces of the United States under dishonorable conditions;

- is a fugitive from justice; or

- having been a citizen of the United States, has renounced that citizenship.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 131 (d)

Training Requirements

An applicant must complete a course that covers at least the following topics:

- the safe use, handling and storage of firearms;

- methods for securing and childproofing firearms;

- the applicable laws relating to the possession, transportation and storage of firearms;

- knowledge of operation, potential dangers and basic competency in the ownership and use of firearms;

- injury and suicide prevention and harm reduction education;

- applicable laws relating to the use of force;

- disengagement tactics; and

- live firearms training.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 131P (b) (ii)

(d) A lawful resident 21 years of age or older residing within the jurisdiction of the licensing authority or any law enforcement officer employed by the licensing authority or any person residing in an area of exclusive federal jurisdiction located within a city or town may submit to the licensing authority an application for a license to carry firearms, or renewal of the same, which the licensing authority shall issue as provided under section 121F only if it appears that the applicant is neither a prohibited person nor determined to be unsuitable to be issued a license as set forth in said section 121F, provided that upon an initial application for a license to carry firearms, the licensing authority shall conduct a personal interview with the applicant.

(e) A license to carry firearms shall be valid, unless revoked or suspended, for a period of not more than 6 years from the date of issue and shall expire on the anniversary of the licensee's date of birth occurring not less than 5 years nor more than 6 years from the date of issue. Any license issued to an applicant born on February 29 shall expire on March 1.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 131 (d) & (e)

Permitless Carry Law

The terms “constitutional carry” and “permitless carry” refer to states that have laws allowing individuals to carry a loaded firearm in public without requiring a license or permit.

Reciprocity Agreements

Reciprocity refers to an agreement between states to recognize, or honor, a concealed firearm permit issued by another state.

When you are in another state, you are subject to that state’s laws. Even if a state recognizes your carry permit or allows for permitless carry, the state may have additional restrictions on certain types of firearms, magazines, or ammunition. Take time to learn the law!

State Preemption Laws

State firearm preemption laws are statutes that prevent local governments from enacting or enforcing their own gun regulations that are more restrictive than state law. These laws ensure that firearm regulations remain consistent across the state, preventing a patchwork of different rules in various cities or counties.

Purchase/Transfer Laws

When buying or selling a firearm, both federal and state laws must be followed. Under 18 U.S.C. § 922(a)(5), a private party may sell a firearm to a resident of the same state if two conditions are met: (1) the seller and buyer must be residents of the same state, and (2) the seller must not know or have reasonable cause to believe that the buyer is prohibited from receiving or possessing firearms under federal law, as outlined in 18 U.S.C. § 922(g).

Additionally, a private seller may loan or rent a firearm to a resident of any state for temporary lawful sporting use, provided they meet the same condition of not knowing or having reason to believe the borrower is prohibited under federal law.

In addition to federal law, state laws governing firearm sales must also be followed, as states may impose additional restrictions such as background checks, waiting periods, or bans on specific types of firearms.

(a) A person with a license to carry under section 131 may sell or transfer firearms and ammunition and a person with a firearm identification card under section 129B may sell or transfer rifles and shotguns that are not large capacity or semiautomatic and ammunition to:

- a person with a license to sell issued under section 122;

- a federally licensed firearms dealer; or

- a federal, state or local historical society, museum or institutional collection open to the public, without an annual limit on transfers.

(b) A person with a license to carry under section 131 may sell or transfer firearms and ammunition therefor and a person with a firearm identification card under section 129B may sell or transfer rifles and shotguns that are not large capacity or semi-automatic and ammunition therefor to the following; provided, however, that no more than 4 firearm transfers shall occur per calendar year:

- a person with a license to carry under section 131;

- an exempted person if permitted under section 129C; and

- a person with a firearm identification card under section 129B; provided, however, that for transfers and purchases of firearms that are not rifles and shotguns that are not large capacity or semiautomatic, the transferee shall also have a valid permit to purchase under section 131A.

(c) An heir or devisee upon the death of a firearm or ammunition owner, a person in the military, police officers and other peace officers, a veteran's organization and historical society, museums and institutional collections open to the public may:

- sell or transfer firearms and ammunition therefor, to a federally licensed firearms dealer, or a federal, state or local historical society, museum or institutional collection open to the public; and

- sell or transfer no more than 4 firearms and ammunition therefor per calendar year to:

- a person with a license to carry under section 131;

- an exempted person under section 129C; or

- a person with a firearm identification card under section 129B; provided, however, that for transfers and purchases of firearms that are not rifles and shotguns that are not large capacity or semi-automatic, the transferee shall have a valid permit to purchase under section 131A.

(d) A person with a license to carry under section 131 may purchase or transfer firearms and ammunition therefor from a dealer licensed under section 122 or a person permitted to sell under this section.

(e) A person with a firearm identification card under section 129B who is over 18 years of age may purchase or transfer rifles and shotguns that are not large capacity or semi-automatic and ammunition therefor from a dealer licensed under section 122 or a person permitted to sell under this section.

(f) A bona fide collector of firearms may purchase a firearm that was not previously owned or registered in the commonwealth from a dealer licensed under section 122 if it is a curio or relic firearm as defined in section 121.

(g) All purchases, sales or transfers of a firearm permitted under this section shall, prior to or at the point of sale, be conducted through the electronic firearms registration system pursuant to section 121B. The department of criminal justice information services shall require each person selling or transferring a firearm pursuant to this section to electronically provide, through the electronic firearms registration system, such information as is determined to be necessary to verify the identification of the seller and purchaser and ensure that the sale or transfer complies with this section. Upon submission of the required information, the electronic firearms registration system shall automatically review such information and display a message indicating whether the seller may proceed with the sale or transfer and shall provide any further instructions for the seller as determined to be necessary by the department of criminal justice information services. The electronic firearms registration system shall keep a record of any sale or transfer conducted pursuant to this section and shall provide the seller and purchaser with verification of such sale or transfer.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 128A

Firearm Classification and Accessory Restrictions

COMING SOON!

Magazine Capacity Restrictions

Magazine capacity laws are designed to limit the number of rounds a firearm's magazine can hold, typically restricting it to a certain number of cartridges (e.g., 10 rounds or fewer). Some state laws restrict the amount of rounds that may be placed in a magazine at any given time, while others prevent the mere possession of unloaded magazines capable of accepting more than a certain number of rounds.

"Large capacity feeding device" means (i) a fixed or detachable magazine, belt, drum, feed strip or similar device that has a capacity of, or that can be readily converted to accept, more than 10 rounds of ammunition or more than 5 shotgun shells; or (ii) any part or combination of parts from which a device can be assembled if those parts are in the possession or control of the same person; provided, however, that "large capacity feeding device" shall not include:

- any device that has been permanently altered so that it cannot accommodate more than 10 rounds of ammunition or more than 5 shotgun shells;

- an attached tubular device designed to accept and capable of operating only with .22 caliber rimfire ammunition; or

- a tubular magazine that is contained in a lever-action firearm or on a pump shotgun.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 121

(a) No person shall possess, own, offer for sale, sell or otherwise transfer in the commonwealth or import into the commonwealth an assault-style firearm, or a large capacity feeding device.

(b) Subsection (a) shall not apply to an assault-style firearm lawfully possessed within the commonwealth on August 1, 2024, by an owner in possession of a license to carry issued under section 131 or by a holder of a license to sell under section 122; provided, that the assault-style firearm shall be registered in accordance with section 121B and serialized in accordance with section 121C.

(c) Subsection (a) shall not apply to large capacity feeding devices lawfully possessed on September 13, 1994 only if such possession is:

- on private property owned or legally controlled by the person in possession of the large capacity feeding device;

- on private property that is not open to the public with the express permission of the property owner or the property owner's authorized agent;

- while on the premises of a licensed firearms dealer or gunsmith for the purpose of lawful repair;

- at a licensed firing range or sports shooting competition venue; or

- while traveling to and from these locations; provided, that the large capacity feeding device is stored unloaded and secured in a locked container in accordance with sections 131C and 131L. A person authorized under this subsection to possess a large capacity feeding device may only transfer the device to an heir or devisee, a person residing outside the commonwealth, or a licensed dealer.

(d) Whoever violates this section shall be punished, for a first offense, by a fine of not less than $1,000 nor more than $10,000 or by imprisonment for not less than 1 year nor more than 10 years, or by both such fine and imprisonment, and for a second offense, by a fine of not less than $5,000 nor more than $15,000 or by imprisonment for not less than 5 years nor more than 15 years, or by both such fine and imprisonment.

(e) This section shall not apply to transfer or possession by:

- a qualified law enforcement officer or a qualified retired law enforcement officer, as defined in the Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act of 2004, 18 U.S.C. sections 926B and 926C, respectively, as amended;

- a federal, state or local law enforcement agency; or

- a federally licensed manufacturer solely for sale or transfer in another state or for export.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 131M

Prohibited Areas - Where Firearms Are Prohibited Under State law

Carrying a firearm into a place where firearms are prohibited by state or federal law is a common way for gun owners to find themselves in legal trouble. These places are known as “prohibited areas,” and they can vary greatly from state to state.

Below you will find the list of the places where firearms are prohibited under this state’s laws. Keep in mind, in addition to these state prohibited areas, federal law adds additional places where firearms are prohibited. See the federal law section for a list of federal prohibited areas.

Massachusetts law:

Firearms are prohibited in the following locations.

- Schools, colleges, and universities. (MGL 269.10 (j))

- A place owned, leased, or under the control of state, county or municipal government and used for the purpose of government administration, judicial or court administrative proceedings, or correctional services, including in or upon any part of the buildings, grounds, or parking areas thereof (General Laws Part IV Title I Chapter 269 Section 10 (2) (i))

- Polling locations (General Laws Part IV Title I Chapter 269 Section 10 (2) (ii))

- Logan Airport security zone (Part I - Title XIV - Chapter 90 Section 61)

- Airports (740 CMR 30.04)

- Court facilities

- Casinos (CMR 205 Mass. Reg. 138.20)

- Off-highway vehicles (General Laws Part I Title XIV Chapter 90B Section 26)

- Boston parks (Boston Parks Rules and Regulations Section 2)

Methods of Carry - Open Carry Laws

Open carry and concealed carry refer to two distinct methods of carrying firearms in public. Open carry involves visibly carrying a firearm, typically in a holster, where it is easily seen by others. Concealed carry, on the other hand, involves carrying a firearm in a hidden manner, such as under clothing, so that it is not visible to others.

No Weapons Signs

No weapons" signs are notices posted by businesses or private property owners indicating that firearms or other weapons are not allowed on the premises. The legal impact of these signs varies by state. In some states, these signs have the force of law, meaning that if a person carries a weapon onto the property in violation of the sign, they can face criminal penalties such as fines or arrest. In these states, ignoring a "no weapons" sign can result in legal consequences similar to trespassing.

In other states, however, these signs are merely a business's policy, and while a person carrying a weapon might be asked to leave, there are no legal penalties for entering with a weapon unless they refuse to leave when asked, at which point trespassing laws may apply.

Massachusetts law:

Whoever, without right enters or remains in or upon the dwelling house, buildings, boats or improved or enclosed land, wharf, or pier of another, or enters or remains in a school bus, as defined in section 1 of chapter 90, after having been forbidden so to do by the person who has lawful control of said premises, whether directly or by notice posted thereon, or in violation of a court order pursuant to section thirty-four B of chapter two hundred and eight or section three or four of chapter two hundred and nine A, shall be punished by a fine of not more than one hundred dollars or by imprisonment for not more than thirty days or both such fine and imprisonment. Proof that a court has given notice of such a court order to the alleged offender shall be prima facie evidence that the notice requirement of this section has been met. A person who is found committing such trespass may be arrested by a sheriff, deputy sheriff, constable or police officer and kept in custody in a convenient place, not more than twenty-four hours, Sunday excepted, until a complaint can be made against him for the offence, and he be taken upon a warrant issued upon such complaint.

This section shall not apply to tenants or occupants of residential premises who, having rightfully entered said premises at the commencement of the tenancy or occupancy, remain therein after such tenancy or occupancy has been or is alleged to have been terminated. The owner or landlord of said premises may recover possession thereof only through appropriate civil proceedings.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 266 § 120

Controlled Substance/Alcohol Laws

Most, but not all, states have laws in place that regulate possessing firearms while intoxicated, and individual states will define "intoxicated" differently. In addition to state law, federal law also prohibits the possession of a firearm by any person who is “an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance” as defined by the Controlled Substances Act (“CSA”). There are five different schedules of controlled substances regulated by the CSA, scheduled as I–V. The types of drugs that are regulated range from heroin as a Schedule I substance, to Robitussin AC as a Schedule V substance. Even a gun owner that is prescribed a scheduled drug by a physician can be in legal jeopardy if it is proven that the drug was taken in a frequency or manner other than was prescribed.

Although legal for medicinal or recreational use in many states, marijuana remains classified as a scheduled controlled substance under the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA), codified as 21 U.S.C. § 812. On May 16, 2024, the U.S. Department of Justice published a proposed rule change that would reclassify marijuana from schedule I to a schedule III drug. It is anticipated this rescheduling will formally occur in 2024 or 2025. Unlike schedule I drugs, schedule III drugs may be lawfully prescribed by a licensed physician, and thus the possession of these prescribed drugs does not make the possession of a firearm inherently unlawful the way possession of a schedule I substance would. This means that the rescheduling of marijuana to a schedule III drug would finally allow for the lawful use, possession and purchase of firearms by prescription marijuana users. However, if it is determined that the marijuana is possessed without a prescription, is used in a manner that is not prescribed, or that the individual with the prescription is addicted to marijuana, possession of a firearm would still be a federal offense. Federal law states that a person is addicted to a controlled substance when they have “lost the power of self-control with reference to the use of controlled substance; and any person who is a current user of a controlled substance in a manner other than as prescribed by a licensed physician.”

27 C.F.R. § 478.11, 18 U.S.C. §922(g)(3)

Massachusetts law:

Whoever, having in effect a license to carry firearms issued under section 131 or 131F of chapter 140, while with a percentage, by weight, of alcohol in their blood of eight one-hundredths or greater, or carries on his person, or has under his control in a vehicle, a loaded firearm, as defined in section 121 of said chapter 140, while under the influence of intoxicating liquor or marijuana, narcotic drugs, depressants or stimulant substances, all as defined in section 1 of chapter 94C, or from smelling or inhaling the fumes of any substance having the property of releasing toxic vapors as defined in section 18 of chapter 270 shall be punished by a fine of not more than $5,000 or by imprisonment in the house of correction for not more than two and one-half years, or by both such fine and imprisonment.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 269 § 10H

Vehicle and Transport Laws

Permit reciprocity and other differences between state regulation of firearms can create a difficult landscape for firearm owners to navigate while transporting firearms interstate. In 1968, and again in 1986, Congress set out to help hunters, travelers, and other firearm owners who were getting arrested for merely transporting firearms through restrictive states. To help simplify the complex web of state firearm laws, Congress passed the 1986 Firearm Owners Protection Act (“FOPA”) as part of Senate Bill 2414. The specific “safe harbor” provision of the law, often referred to as the “McClure-Volkmer Rule,” provides some protection for gun owners transporting firearms through restrictive states, subject to strict requirements. This federal law is covered in more detail in the federal law section of this database.

Beyond federal law, the laws of each state will impose additional restrictions, or protections, related to transporting firearms in a vehicle.

(a) No person carrying a loaded firearm under a license issued pursuant to section 129B, 131 or 131F or through an exemption under section 129C shall carry the loaded firearm in a vehicle unless the loaded firearm while carried in the vehicle is under the direct control of the person. Whoever violates this subsection shall be punished by a fine of $500.

(b) No person possessing a large capacity firearm under a license issued pursuant to section 131 or 131F or through an exemption under section 129C shall possess the large capacity firearm in a vehicle unless the large capacity firearm is unloaded and secured in a locked container as defined in section 121. Whoever violates this subsection shall be punished by a fine of not less than $500 nor more than $5,000.

(c) This section shall not apply to: (i) an officer, agent or employee of the commonwealth, any state or the United States; (ii) a member of the military or other service of any state or of the United States; (iii) a duly authorized law enforcement officer, agent or employee of a municipality of the commonwealth; provided, however, that a person described in clauses (i) to (iii), inclusive, is authorized by a competent authority to carry or possess the firearm so carried or possessed and is acting within the scope of the person's official duties.

(d) A conviction of a violation of this section shall be reported immediately by the court or magistrate to the licensing authority. The licensing authority shall immediately revoke the firearm identification card or license of the person convicted of a violation of this section. No new firearm identification card or license may be issued to a person convicted of a violation of this section until 1 year after the date of revocation of the firearm identification card or license.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 131C

Storage Requirements

Some states have laws that require gun owners to take specific measures to secure their firearms, especially in households with children. Many of these state laws mandate that guns be stored in locked containers or safes when not in use. These laws often impose penalties for failing to secure firearms, particularly if they are accessed by unauthorized individuals, such as minors.

Massachusetts law:

It shall be unlawful to store or keep any firearm in any place unless such firearm is secured in a locked container or equipped with a tamper-resistant mechanical lock or other safety device, properly engaged so as to render such firearm inoperable by any person other than the owner or other lawfully authorized user. It shall be unlawful to store or keep any stun gun in any place unless such firearm is secured in a locked container accessible only to the owner or other lawfully authorized user. For purposes of this section, such firearm shall not be deemed stored or kept if carried by or under the control of the owner or other lawfully authorized user.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 131L (a)

Other Weapons Restrictions

COMING SOON!

Police Encounter Laws

Some states impose a legal duty upon permit holders that requires them to inform a police officer of the presence of a firearm whenever they have an official encounter, such as a traffic stop. These states are called “duty to inform” states. In these states you are required by law to immediately, and affirmatively, tell a police officer if you have a firearm in your possession.

In addition to “duty to inform states,” some states have “quasi duty to inform” laws. These laws generally require that a permit holder have his/her permit in their possession and surrender it upon the request of an officer. The specific requirements of these laws will vary from state to state.

The final category of states is classified as “no duty to inform” states. In these states there are no laws that require a gun owner to affirmatively inform an officer if they have a firearm. Additionally, there are also generally no laws that require you to respond or provide a permit if asked about the presence of a firearm.

Massachusetts is a quasi-duty-to-inform state.

Massachusetts law:

Any person who, while not being within the limits of his own property or residence, or such person whose property or residence is under lawful search, and who is not exempt under this section, shall on demand of a police officer or other law enforcement officer, exhibit his license to carry firearms, or his firearm identification card or receipt for fee paid for such card, or, after January first, nineteen hundred and seventy, exhibit a valid hunting license issued to him which shall bear the number officially inscribed of such license to carry or card if any. Upon failure to do so such person may be required to surrender to such officer said firearm, rifle or shotgun which shall be taken into custody as under the provisions of section one hundred and twenty-nine D, except that such firearm, rifle or shotgun shall be returned forthwith upon presentation within thirty days of said license to carry firearms, firearm identification card or receipt for fee paid for such card or hunting license as hereinbefore described. Any person subject to the conditions of this paragraph may, even though no firearm, rifle or shotgun was surrendered, be required to produce within thirty days said license to carry firearms, firearm identification card or receipt for fee paid for such card, or said hunting license, failing which the conditions of section one hundred and twenty-nine D will apply. Nothing in this section shall prevent any person from being prosecuted for any violation of this chapter.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 129C

Red Flag or Emergency Risk Orders

Emergency Risk Orders (or "Red Flag Laws") enable rapid legal action when someone is believed to be at significant risk of harming themselves or others with a firearm. Generally speaking, these controversial laws allow law enforcement to seek a court order to temporarily confiscate firearms from the individual and prevent them from purchasing new ones while the order is in effect. The most robust laws also permit family members and others to file petitions.

(a) A petitioner who believes that a person may pose a risk of causing bodily injury to self or others may, on a form furnished by the court and signed under the pains and penalties of perjury, file a petition in court.

(b) A petition filed pursuant to this section shall:

- state any relevant facts supporting the petition;

- identify the reasons why the petitioner believes that the respondent poses a risk of causing bodily injury to self or others by having in the respondent's control, ownership or possession a firearm or ammunition;

- identify the number, types and locations of any firearms or ammunition the petitioner believes to be in the respondent's current control, ownership or possession;

- identify whether there is an abuse prevention order pursuant to chapter 209A, a harassment prevention order pursuant to chapter 258E or an order similar to an abuse prevention or harassment prevention order issued by another jurisdiction in effect against the respondent; and

- identify whether there is a pending lawsuit, complaint, petition or other legal action between the parties to the petition.

(c) No fees for filing or service of process may be charged by a court or any public agency to a petitioner filing a petition pursuant to this section.

(d) The petitioner's residential address, residential telephone number and workplace name, address and telephone number, contained within the records of the court related to a petition shall be confidential and withheld from public inspection, except by order of the court; provided, however, that the petitioner's residential address and workplace address shall appear on the court order and shall be accessible to the respondent and the respondent's attorney unless the petitioner specifically requests, and the court orders, that this information be withheld from the order. All confidential portions of the records shall be accessible at all reasonable times to the petitioner and the petitioner's attorney, the licensing authority of the municipality where the respondent resides and to law enforcement officers, if such access is necessary in the performance of their official duties. Such confidential portions of the court records shall not be deemed to be public records under clause twenty-sixth of section 7 of chapter 4.

(e) The court may order that any information in the petition or case record be impounded in accordance with court rule.

(f) Upon receipt of a petition under this section and if the petitioner is a family or household member as defined in section 121, the clerk of the court shall provide to the petitioner and respondent informational resources about:

- crisis intervention;

- mental health;

- substance use disorders;

- counseling services; and

- the process to apply for a temporary commitment under section 12 of chapter 123.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 131R

(a)

- Upon the filing of a petition pursuant to section 131R, the court may issue an emergency extreme risk protection order without notice to the respondent and prior to the hearing required pursuant to subsection (a) of section 131S if the court finds reasonable cause to conclude that the respondent poses a risk of causing bodily injury to the respondent's self or others by being in possession of a license to carry firearms or a firearm identification card or having in the respondent's control, ownership or possession a firearm or ammunition. Upon issuance of an emergency extreme risk protection order pursuant to this section, the clerk magistrate of the court shall notify the respondent pursuant to subsection (e) of section 131S. An order issued under this subsection shall expire 10 days after its issuance unless a hearing is scheduled pursuant to subsection (a) or (b) of said section 131S or at the conclusion of a hearing held pursuant to said subsection (a) or (b) of said section 131S unless a permanent order is issued by the court pursuant to paragraph (2) of subsection (c) of said section 131S.

- Upon receipt of service of an extreme risk protection order pursuant to this section, the respondent shall immediately surrender the respondent's license to carry firearms or firearm identification card and all firearms or ammunition to the local licensing authority serving the order as provided in subsection (f) of section 131S.

(b)

- If the court has probable cause to believe that the respondent has access to a firearm or ammunition, on their person or in an identified place, and the respondent fails to surrender any firearms or ammunition within 24 hours of being served pursuant to subsection (e) of section 131S, the court shall issue a warrant identifying the property, naming or describing the person or place to be searched, and commanding the appropriate law enforcement agency to search the person of the respondent and any identified place and seize any firearm or ammunition found to which the respondent would have access.

- The law enforcement agency shall conduct its search and manage any seized property pursuant to paragraph (3) of subsection (d) of section 131S.

(c) When the court is closed for business, a justice of the court may grant an emergency extreme risk protection order if the court finds reasonable cause to conclude that the respondent poses a risk of causing bodily injury to the respondent's self or others by being in possession of a license to carry firearms or firearm identification card or by having in the respondent's control, ownership or possession of a firearm or ammunition, and shall issue a warrant pursuant to subsection (b) upon probable cause that the respondent has access to a firearm or ammunition, on their person or in an identified place, and the respondent fails to surrender any firearms or ammunition within 24 hours of being served pursuant to subsection (e) of section 131S. In the discretion of the justice, such relief may be granted and communicated by telephone to the licensing authority of the municipality where the respondent resides, which shall record such order or warrant on a form of order or warrant promulgated for such use by the chief justice of the trial court and shall deliver a copy of such order or warrant on the next court business day to the clerk-magistrate of the court. If relief has been granted without the filing of a petition pursuant to section 131R, the potential petitioner shall appear in court on the next available court business day to file a petition. An order or warrant issued under this subsection shall expire at the conclusion of the next court business day after issuance unless said potential petitioner has filed a petition with the court pursuant to section 131R and the court has issued an emergency extreme risk protection order pursuant to subsection (a).

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140 § 131T

Use of Force in Defense of Person

The legal use of force, including deadly force, is regulated by state law. There are no federal laws that dictate when you can use force in self-defense in all states. As such, it is essential to become familiar with individual state laws.

Massachusetts law:

Under Massachusetts law, you are justified in using deadly force in self-defense if you have taken every opportunity to avoid combat and have a reasonable ground to believe, and actually do believe that you are in imminent danger of death or serious bodily injury.

Commonwealth v. Berry, 727 N.E.2d 517 (Mass. 2000); Mass. Crim. Model Jury Instructions No. 9.260.

Admissibility of evidence of physical, sexual or psychological abuse and related expert testimony

In the trial of criminal cases charging the use of force against another where the issue of defense of self or another, defense of duress or coercion, or accidental harm is asserted, a defendant shall be permitted to introduce either or both of the following in establishing the reasonableness of the defendant's apprehension that death or serious bodily injury was imminent, the reasonableness of the defendant's belief that he had availed himself of all available means to avoid physical combat or the reasonableness of a defendant's perception of the amount of force necessary to deal with the perceived threat:

- evidence that the defendant is or has been the victim of acts of physical, sexual or psychological harm or abuse;

- evidence by expert testimony regarding the common pattern in abusive relationships; the nature and effects of physical, sexual or psychological abuse and typical responses thereto, including how those effects relate to the perception of the imminent nature of the threat of death or serious bodily harm; the relevant facts and circumstances which form the basis for such opinion; and evidence whether the defendant displayed characteristics common to victims of abuse.

Nothing in this section shall be interpreted to preclude the introduction of evidence or expert testimony as described in clause (a) or (b) in any civil or criminal action where such evidence or expert testimony is otherwise now admissible.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 233 § 23F

Use of Force in Defense of Others

Defense of third party laws allow an individual to use force, including deadly force, to protect another person from harm. These laws generally permit intervention if the third party would have had the right to use force in their own self-defense under the same circumstances. The exact application of these laws will vary by jurisdiction, so it is important to understand the framework of each individual state.

Under Massachusetts law, you may use reasonable force, including deadly force, when necessary to help another person, if it reasonably appears under the circumstances that the person being aided would be justified in using force in self-defense and your aid is reasonably necessary to protect such person.

Commonwealth v. Martin, 341 N.E.2d 885 (Mass. 1976); Mass. Crim. Model Jury Instructions No. 9.260.

Use of Force in Defense of Habitation

The term "castle doctrine" comes from English common law providing that one's abode is a special area in which one enjoys certain protections and immunities, from which one is not obligated to retreat before defending oneself against attack, and in which one may do so without fear of prosecution.

Many states have instituted castle doctrine laws, with varying degrees of formality. Some states have statutorily enacted castle doctrine laws, some have judicially-created protections (called “common laws”), while others have no amplified protections in the home at all.

Massachusetts law:

In the prosecution of a person who is an occupant of a dwelling charged with killing or injuring one who was unlawfully in said dwelling, it shall be a defense that the occupant was in his dwelling at the time of the offense and that he acted in the reasonable belief that the person unlawfully in said dwelling was about to inflict great bodily injury or death upon said occupant or upon another person lawfully in said dwelling, and that said occupant used reasonable means to defend himself or such other person lawfully in said dwelling. There shall be no duty on said occupant to retreat from such person unlawfully in said dwelling.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 278 § 8A

Use of Force in Defense of Property

Generally speaking, the use of deadly force is limited to circumstances that reasonably present an imminent threat of serious bodily injury or death of a human being. As such, using deadly force in defense of mere personal property is almost categorically prohibited. Although most states will allow the use of some amount of force (i.e. physically restraining someone until the police arrive), the use or threatened use of deadly force in defense of mere property is generally not permitted.

You may NEVER use deadly force to protect your property in Massachusetts. You may only use reasonable force to defend your personal property from theft or destruction and real property from an intruder or trespasser. The force used must be appropriate in kind and suitable in degree, and not more than reasonably necessary to defend your property. In Commonwealth v. Donahue, 20 N.E. 171 (Mass. 1889), the Massachusetts Supreme Court stated that "a man may defend or regain his momentarily interrupted possession by the use of reasonable force, short of wounding or the employment of a dangerous weapon." What is reasonable in each situation varies. However, a person who uses force that is clearly excessive and unreasonable becomes the aggressor and loses the right to defend his or her property.

Commonwealth v. Haddock, 704 N.E.2d 537 (Mass. App. Ct. 1999); Mass. Crim. Model Jury

Instructions No. 9.260.

Self-Defense Immunity

COMING SOON!

Duty to Retreat

A duty to retreat is an obligation to flee that is imposed upon a civilian who is under attack. If applicable, it applies to the victim of unlawful force prior to their ability to use deadly force to defend him or herself. The duty to retreat makes self-defense unavailable to those who use deadly force when they could have retreated from the confrontation safely. The alternative to duty-to-retreat laws is no-duty-to-retreat laws or stand-your-ground laws as they’re commonly called. Stand-your-ground states impose no duty to flee upon victims and instead state that one can stand their ground and meet force with force, under certain situations.

Massachusetts has a "duty to retreat"! If you have an opportunity to retreat but fail to do so, you have no privilege to use force in self-defense. A person must generally use all proper means of escape before resorting to physical combat, except under certain circumstances.

Commonwealth v. Niemic, 696 N.E.2d 117 (Mass. 1998).

Self-Defense Limitations

COMING SOON!

Use of Force Considerations

COMING SOON!

Use of Force Against Animals

A person may kill a dog found outside the enclosure of its owner or keeper which suddenly assaults the person while he or she is peaceably standing, walking, or riding; and any person may kill a dog found out of the enclosure of its owner or keeper and not under his immediate care in the act of worrying, wounding, or killing persons, livestock, or fowls. The person will not be held liable for cruelty to the dog, so long as the person does not intend to be cruel and does not act with a wanton and reckless disregard for the suffering of the dog.

However, a person who kills or wounds a dog under these conditions must promptly report such killing or wounding to the owner, animal control office, or police officer.

Massachusetts law does not directly address defending against other animal attacks, but it is likely a person would have a strong defense if they were charged with animal cruelty and they acted without any intent to be cruel, wanton, or reckless.

In either case, a person must not intentionally or knowingly commit acts plainly of a nature to inflict unnecessary pain upon an animal.

Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 140, $ 156; Commonwealth v. Linhares, 957 N.E.2d 243 (Mass. App. Ct. 2011)

Cases to Watch

COMING SOON!

Latest Updates

08/05/2025 Update:

- A petition (accompanied by bill, House, No. 2590) to amend MGL c. 140 § 129C.

*PENDING HB2590: An Act making firearm owners civilly liable for damage caused by lost or stolen firearms. Whoever fails to report the loss or theft of a firearm, rifle, shotgun or machine gun that is later used in the commission of a crime shall be civilly liable for any damages resulting from that crime. The liability imposed under this paragraph shall not apply if the owner reports the loss or theft of such firearm, rifle, shotgun or machine gun to the commissioner of the department of criminal justice information services and the licensing authority in the city or town where the owner resides within 24 hours of the owner’s knowledge of such loss or theft.

01/23/2026 Update:

- HB4885: An Act Modernizing Firearms Laws. Under this act, which was signed into law in July 2024, Massachusetts is implementing mandatory live-fire training for new License to Carry (LTC) and Firearm Identification Card (FID) applicants, with a final compliance deadline of April 2, 2026. While some provisions of the law took effect in October 2024, the specific, strict live-fire certification requirement for all applicants becomes mandatory on this date.